American Deindustrialization

Part 3 of the American economy series focuses on the effects of offshoring manufacturing supply chains

Tl;dr

· The US industrial base responded differently to COVID-19 than WW2

· Deindustrialization in the US increased sharply in the first decades of the 21st century

· Industries exposed to international trade, particularly with China, have shrunken in the US

· The US is not as competitive as it could be

· Deindustrialization in the US destroys communities, shortens life spans, harms the environment and threatens our national security

SUBSCRIBE HERE:

In December 1940, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt took to the airwaves to address the American people about the deteriorating situation in Europe. Hitler had invaded Poland in 1939 and the specter of totalitarianism loomed over all the continent. “We must be the great arsenal of democracy”[i] he said, referring to the need to unleash America’s awesome industrial capacity. The economy went on a war footing. Detroit, the center of American manufacturing, stopped making civilian automobiles and started making bombers, tanks, and other weapons.[ii] Five years later, after America had armed its allies in Europe, the Soviet Union, and itself, it won WW2 handily. Thanks to America’s manufacturing dominance, it wasn’t even that close.

Figure 1: Vast Allied invasion fleet on D-Day off the coast of France, all made in the USA

Eighty years later in March 2020, an unknown respiratory virus ripped through Detroit. The city had endured a lot in those past eight decades including economic collapse, population decline, and an unprecedented municipal bankruptcy after the auto plants closed down and moved to cheaper jurisdictions abroad. The city was especially vulnerable to the novel coronavirus.

One nurse practitioner who works at several hospitals in the Detroit area described dire scenes unfolding.

Hospitals in the Detroit Medical Center network are putting two patients at a time into intensive care unit rooms that are made for one patient, she said. Because of a shortage of equipment, some patients are hooked to portable monitors that cannot be monitored in a single, central system.

“Every day I drive home, I start crying,” said the nurse, who asked that her name not be used for fear of losing her job. “I’ve been in health care for 20 years and I’ve never seen anything like this.”[iii]

In Detroit and elsewhere across the US, front-line workers ran out of essential PPE like gowns and masks and couldn’t get more because the plants that made them had been offshored. Nurses improvised, using trash bags as gowns and reusing masks. Some of them died.

As of September 2022, Wayne County where Detroit is, had the 9th highest death toll from the COVID-19 pandemic in the nation[iv].

Deindustrialization in US

Manufacturing job losses are not new in America. Manufacturing employment peaked in the 1970s at almost 20 million jobs. Some of these losses are heathy, as firms became more productive and deployed things like automation. But in the first decade of the 21st century, manufacturing jobs plummeted from 17 million in January 2001 to 11 million in January 2010.[v]

Figure 2: US manufacturing jobs get sucked out of the US in the first decade of the 21st century[vi]

Manufacturing also became a smaller slice of the economy, falling from a peak of close to a third to 11% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a measure of all goods and services sold in the economy. But that could mean that manufacturing’s relative share of GDP shrank; the rest of the economy could have grown while manufacturing stayed the same.

Figure 3: Manufacturing's share of the economy has fallen since the mid-twentieth century[vii]

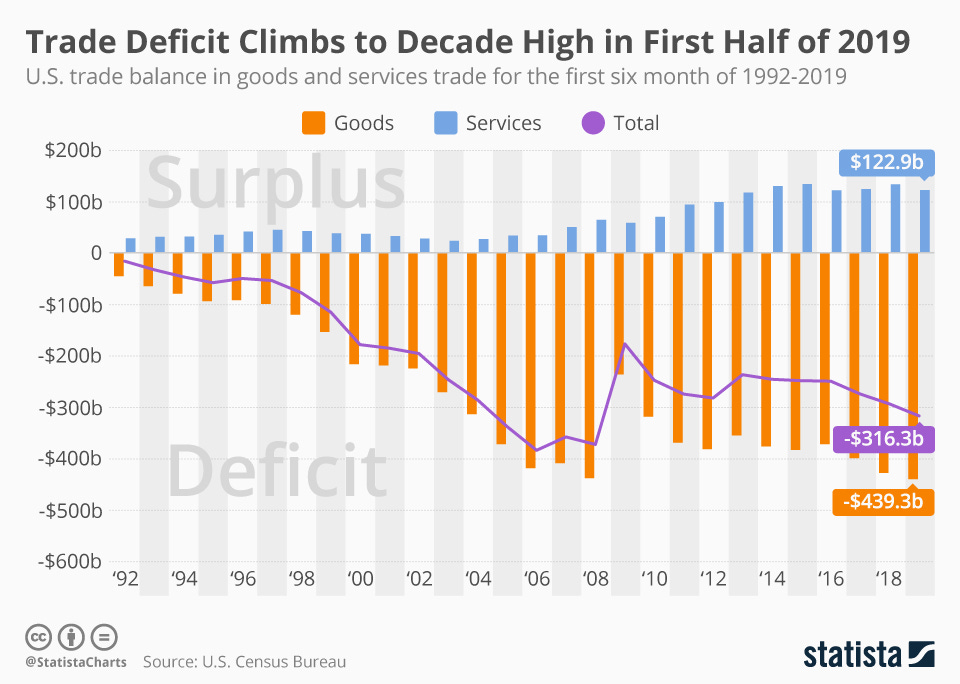

Alas, that’s not what happened. As Figure 4 shows, the US’ trade deficit has ballooned in the first decades of the 21st century. This means people in the US have to import what they need from foreign countries. America doesn’t make things like it used to.

Figure 4: The US trade deficit grew drastically in the early 21st century[viii]

Impact of Free Trade

Much of US manufacturing left for low-cost international destinations in the Era of Globalization after WW2. At the Breton Woods Conference in 1944, the US created a new security and economic order that allowed manufacturing supply chains to wrap around the world. For the first time, firms could put plants wherever labor costs were lowest or tax rules were most favorable, and sell their products into any market in the world. In Detroit, many auto plants went to Mexico or across the Ambassador Bridge to Canada after the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect in 1994.

But by far the largest cause of American deindustrialization was the rise of China. In the 1990s, millions of peasants moved from the countryside to the cities for jobs in the largest migration in human history[ix]. Then in 2001, China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO), facilitating economic integration with the world. Researchers from MIT have determined that not only did the US jobs leave when exposed to trade with China, but communities remained depressed for more than a decade afterward.

Adjustment in local labor markets is remarkably slow, with wages and labor-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China trade shock commences.[x]

As a whole, the US economy has not been competitive when exposed to international trade. Industries exposed to international trade, which offer on average better paying jobs, have shrunken since 2000. The rest of the economy has grown.

Figure 5: The stagnation of US industry exposed to trade[xi]

US Competitiveness

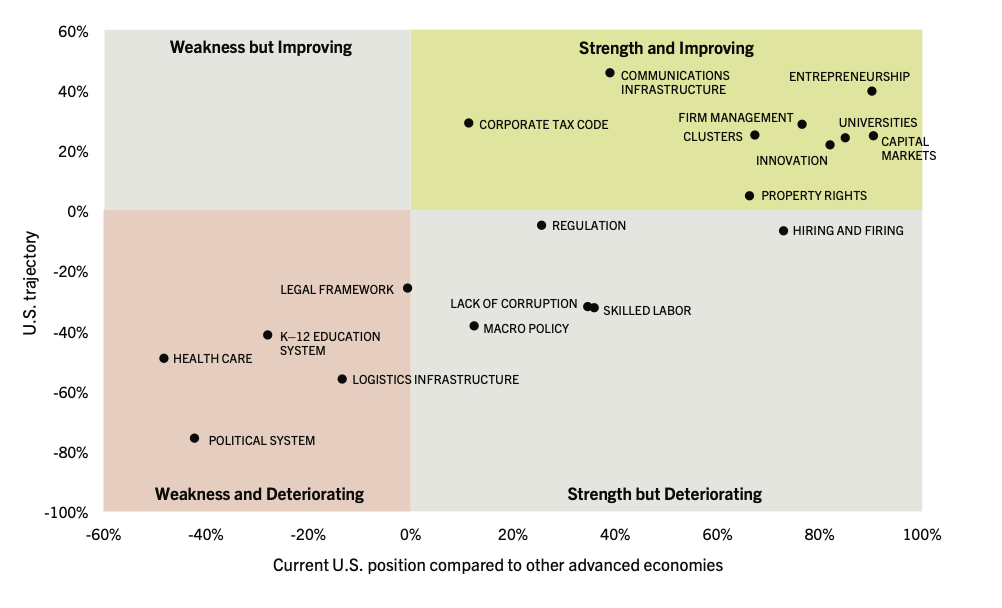

Another way to think about these manufacturing job losses was that the US wasn’t competitive enough to retain these jobs in the face of international competition. Business executives picking the location for the next manufacturing plant is a bit like a global version of team captains picking teams for a playground basketball game. But instead of height, speed, and dribbling ability they’re looking for things like labor cost, regulatory environment, and logistics infrastructure. And labor costs. Figure 6 shows the US’ strengths and weaknesses, as assessed by a Harvard Business School survey.

Figure 6: US strengths and weaknesses[xii]

The US is never going to have the lowest labor costs in the world, nor should that be its goal. But it’s the largest consumer market in the world and locating plants here should reduce transportation costs well below shipping goods from China. And the US could have the lowest electricity costs in the world, if it fully unleashed natural gas drilling, or wind power in the Midwest, or solar power in the Southwest. Every decision the government makes should be about making America the best player in the global pickup game of manufacturing. That’s not the current mindset.

Consequence 1: Loss of Social Cohesion

When a plant closes down, it doesn’t just mean job losses for those workers. It’s the death of that community. When workers are unemployed, the tax base collapses. That means local government can’t pay for things like the police department, the fire department, or roads. Hospitals no longer have insured patients to treat. Homes are foreclosed and abandoned, leading to collapsing home values and wealth destruction for the entire community. Main street shops and restaurants that used to serve middle class workers lose their customers and have to close down. The downward cycle that occurs when a plant leaves town is like an endless doom loop.

Figure 7: Abandoned home somewhere in the interior of the US

Unemployed, these workers (families really) become drains on government unemployment resources. They represent a growing, dissatisfied voting bloc that isn’t going away until the root of these problems is addressed. The problems felt in these communities will continue to metastasize across the entire nation. Faced with no job, workers often turn to drugs, alcohol, or suicide.

Consequence 2: Deaths of Despair

In 2022, the CDC released new data showing that the average US life span is now less than the average Chinese lifespan.[xiii] Part of this is COVID-19, but part of it follows a disturbing trend of stagnant to declining life spans in the US versus its rich world peers.

Figure 8: US life expectancy versus advanced countries

I would argue that life expectancy is a country’s single most important metric. If a rich country can’t keep its citizens healthy, what else matters? The US is failing at this objective and the decrease in life span correlates perfectly with an increase in Deaths of Despair (alcohol-, drug-related, or suicides) in the first decades of the 21st century (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Deaths of Despair in the US[xiv]

The opioid epidemic rages in the areas hit hardest by deindustrialization. Likewise, alcohol-related deaths and suicides overlap with the geography of the Rust Belt. Without jobs, humans have no purpose, hope, and are driven to drink, pills, and suicide.

Consequence 3: Environmental Deterioration

One of the factors that business leaders look to when deciding where to put a plant is environmental regulation, or lack thereof. One of the ways that China is so “competitive” is extremely lax environmental law. Firms there don’t have to install expensive pollution control devices required in the US. In a sense we’ve exported our pollution there, to the Chinese populace’s detriment.

Figure 10: Pollution in Baoding, China[xv]

We don’t want to remove environmental regulation in the US, which has been very good for us and the planet. But some permitting reform can make the US more competitive and save the planet. Take for instance the time it takes to get an environmental permit from the government:

By 2010, the average government-wide completion time became 4.2 years, and by 2016, the average had grown to over five years. This means that the average amount of time needed to get permission to build a project is now longer than the total time it took— from start to finish—to build the Hoover Dam or the Golden Gate Bridge. [xvi]

If you care about CO2 emissions and climate change, you should care about offshoring to China. The thing about global warming, is that it’s global. It doesn’t matter where on the earth the CO2 is generated, the effect is the same. Since China joined the WTO in 2001, its CO2 emissions have rocketed to almost twice that of the US. That’s partly because China uses a much higher portion of coal plants than the US to generate the electricity it uses to make things. Deindustrialization is killing the US, and the planet.

Figure 11: CO2 emissions in the US and China[xvii]

Consequence 4: Decreased National Security

Figure 12: Ukrainian military fires Western-made artillery[xviii]

What if FDR had given the “Arsenal of Democracy” speech and there was no response? The US would have lost WW2 and this article would be written in German. A country that no longer makes things is a country that can’t mobilize for an emergency. Speed is also a factor. The US was ultimately able to make medical PPE to fight COVID-19, but on a timeline that was too late for thousands. Likewise, there have been some reports that the US is running low on the arms it’s sending to its ally Ukraine and that replacements will take years to produce.[xix] By then, it may be too late for Ukraine on the battlefield. To remain secure, America needs a thriving industrial base.

Up Next

Thanks for reading American Deindustrialization in this multipart series on the American economy. Up next is how monopolies are rigging the economy.

Author’s note: several of you have reached out to me about including potential solutions to these problems, like in prior posts. Those are coming in the final installment of this series.

SUBSCRIBE HERE:

[i] https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/fdrarsenalofdemocracy.html

[ii] Baime, A. J. The Arsenal of Democracy: FDR, Detroit, and an Epic Quest to Arm an America at War. Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015.

[iii] New York Times

[iv] Johns Hopkins

[v] BLS

[vi] BLS

[vii] US Bureau of Economic Analysis

[viii] US Census Bureau

[ix] E., Goodhart C A, and Manoj Vasant Pradhan. The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival. Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

[x] Autor, David H.; Dorn, David; Hanson, Gordon H. (2016-10-31). "The China Shock: Learning from Labor-Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade". Annual Review of Economics.

[xi] Porter, Michael E., Jan Rivkin, Mihir Desai, and Manjari Raman. "Problems Unsolved and a Nation Divided: The State of U.S. Competitiveness 2016." Report, U.S. Competitiveness Project, Harvard Business School, September 2016.

[xii] Porter, Michael E., Jan Rivkin, Mihir Desai, Katherine M. Gehl, William R. Kerr and Manjari Raman. "A Recovery Squandered: The State of U.S. Competitiveness 2019." Report, U.S. Competitiveness Project, Harvard Business School, December 2019.

[xiii] CDC

[xiv]CDC

[xv] The Guardian

[xvi] Murray, William. “Costs, Benefits, and Unintended Consequences: Environmental Law and Deindustrialization.” American Affairs, vol. 5, no. 4, Winter 2021, pp. 98–114.

[xvii] The Guardian

[xviii] Bangkok Post

[xix] https://www.csis.org/analysis/united-states-running-out-weapons-send-ukraine