How to fix inflation and lower prices at the pump

The solution is quickly increasing the supply of domestic energy using the Defense Production Act

Tl;dr

· Energy costs are driving the recent spike in inflation

· Reductions in US oil and gas supply from the COVID-19 pandemic are causing energy prices to increase

· The US Government should invoke the Defense Production Act to increase the supply of domestic oil and gas

· Not doing so exposes the US to Russia using the oil weapon and dramatically raising the price of oil

Inflation and energy

Inflation is a big topic in the economy today. In the first half of 2022, inflation has been running at a 40-year high. Last week, the Labor Department released data showing that consumer prices rose 9.1% in June. That means on average, buying things in your life cost 9.1% more than in June 2021. You’ve probably heard many causes: supply-chains, the war in Ukraine, a wage-price spiral. Those things are all true but the biggest cause is the same issue that caused major inflation 40 years ago: rising energy costs.

The Labor Department measures inflation by constructing a hypothetical basket of goods that is intended to replicate what the average consumer buys each month. Each item is then weighted based on how much the average person spends. For example, housing is given a greater weight than clothing. Energy costs are directly measured by categories like utilities and fuel. Those items can be broken out and show that direct energy price increases make up the largest part of the price increases we’ve seen lately (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Direct energy costs contribution to CPI[1]

But this understates the contribution of energy to inflation because energy costs are embedded in everything we consume in modern life. The computer or smart device you’re reading this on is probably made of plastic, which was derived from crude oil. It was probably made in Asia, meaning it was transported to you on a container ship requiring fuel oil, and then delivered to you on a truck running on diesel fuel. That coffee you had this morning was made from beans sourced in Guatemala, which had to be roasted (energy) and transported to you (energy). Even if you don’t drink coffee, you certainly eat and the farmer who grew that food probably drove a tractor (energy) and…you get the idea. So, the measurement of energy’s contribution to inflation by direct costs such as fuel and utilities understates the case.

Energy markets are complex but the price of crude oil and natural gas are good proxies for overall energy costs. Those prices have surged over the past few years (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Oil and natural gas prices in the US[2]

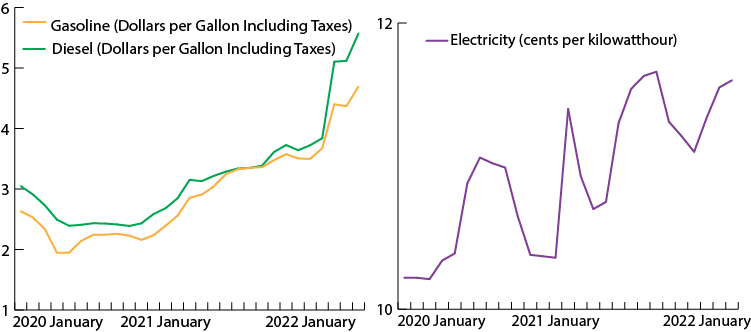

But you can’t use raw crude oil or natural gas directly. Crude oil is refined into gasoline and diesel in a refinery (you can learn how here, if you’re interested). Natural gas is burned to make electricity at power plants. Other raw sources (like coal, wind, and hydroelectric dams) also are used to produce electricity in the US, but natural gas is the biggest source. As one would expect, the price of these end products has tracked their underlying commodity inputs upwards (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Consumer energy prices[3]

Unconventional energy in the United States

Energy prices are determined by global supply and demand. Historically, a large part of the supply came from the Middle East. Additionally, it came from conventional reservoirs, which are essentially large pools of fossil fuels trapped deep in the earth. To produce them, a well is simply drilled into them and the natural pressure of the reservoir pushes the oil and gas to the surface. Then in the 2000s, the energy industry figured out a way to produce unconventional reservoirs in North America. You may have heard of this as shale production or the process as “fracking”. A comparison of these techniques is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Conventional vs unconventional resources[4]

In the long-term, this will have dramatic geopolitical consequences, but in the short-term (the last two decades) it produced a glut of oil and gas. The US produced so much that it went from importing oil from the Middle East to becoming a net-exporter (achieving energy independence). Figure 5 shows the dramatic increase in oil and gas production in the US.

Figure 5: Oil and gas production in the US since 2000[5]

The shale revolution only happened in the US because of a mix of factors that only America has: 1) the correct geology, 2) private property rights, 3) existing oil and gas infrastructure, 4) a mature oil and gas service sector and 5) deep capital markets. The last factor (deep capital markets) was particularly important because unconventional production is far more capital intensive than conventional production. Producers have two ways to raise money to drill unconventional wells: they can issue stock or issue debt. In the case of stock, the producer issues shares of ownership in the company to investors on the stock market. In exchange for those shares, investors provide the producer with cash. In return, investors expect the value of their shares to increase as the company becomes more valuable. In the case of debt, producers issue bonds (essentially like a home mortgage) to investors and get cash. In return, investors get predetermined interest payments periodically for loaning the producer their money.

In the spirit of a classic Texas oil boom and bust, things got a little out of hand. In the first decade-and-a-half of the shale boom, investors lost their shirts. Over that period, shale producers returned an estimated -$300 billion to investors for all stocks and debt (see Figure 6). That means investors lost a cumulative $300 billion. Since investor’s goal is typically to make money, they told shale producers that they needed to be more responsible with their money. They demanded a higher return and company executives agreed, restraining their future drilling programs.

Figure 6: Cash flow return to investors[6]

COVID-19 Pandemic

Just as investors were having their “come to Jesus” discussions with shale producers, a pandemic hit. This and the subsequent lockdowns tanked the demand for energy as planes stopped flying, traffic thinned and most work moved to remote. Shale producers slashed their drilling programs, and US oil production fell by 3 million barrels per day almost overnight (Figure 4). It still has not returned to pre-pandemic levels, in part because shale producers internalized messages from investors about being more disciplined stewards of their capital. This reduction in supply is part of what has caused the recent rise in energy prices.

US Government Response

To date, the US government response has been to release oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) in an effort to increase the supply of crude oil and lower prices. The SPR is a series of caverns in Texas and Louisiana managed by the Department of Energy (DOE) as an emergency stockpile established after the 1973 Arab Oil Embargo. At 714 million barrels, it is the largest such stockpile in the world. Currently, the DOE is releasing about 1 million barrels per day and the effect has been negligible on oil prices (Figure 7).

Figure 7: SPR inventory level[7]

Recommended Action

I believe the US government should mobilize all of its resources and take the following actions to reduce the price of energy and inflation in the US.

1. Increase the supply of oil and gas in the US by:

a. Using the Defense Production Act to offer $100 billion in interest-free loans to shale producers to immediately deploy into drilling campaigns. The loans cannot be used for executive bonuses or share buybacks and will be audited by an Inspector General.

b. Guaranteeing shale producers the greater of $80/barrel or the market spot price for their production to refill the SPR.

The $100 billion in interest-free loans is meant to obviate shale producer’s hesitancy in ramping up production in order to provide a high rate of return to investors. This is not an unprecedented step by the federal government, who offered interest-free loans to establish domestic aluminum and titanium industries during the Cold War[8].

Another reason shale producers are hesitant to ramp up production is that they aren’t sure the market price for oil and gas will stay high or collapse (perhaps due to a recession). For example, if oil costs $60/barrel to produce and the market price stays at the current $100/barrel, a producer stands to profit $40/barrel for every barrel produced. But if the market price falls to $40/barrel, the producer will lose $20/barrel. By guaranteeing the greater of $80/barrel or the market spot price, the US government will de-risk the business for shale producers and incentivize drilling. With 193 million barrels to fill in the SPR, that is a $15 billion incentive to the shale industry.

As shown in this post, decreasing the price of energy will reduce the bulk of inflation. Enacting this plan by employing the Defense Production Act will increase the supply of oil and gas and decrease the price of energy.

Putin’s oil weapon

But isn’t this the government intervening in free markets? Yes it is. By intervening in free markets, the government can and often does distort them with negative outcomes. And the market will correct the present situation if given time. The question is, how much time? The US government should intervene on national security grounds to expedite the process.

Oil demand is unique as a product in that its demand is inelastic. For a typical good, raising the price reduces its demand. For example, say a concert ticket is $5 and everyone wants to go. But say the venue raises ticket prices to $100 and demand drops precipitously. Only the most hardcore fans want to go. The demand for concert tickets is elastic. In contrast, oil makes much of modern life possible. When the price of oil goes up, we can’t turn off electricity, quit driving, or stop the modern economy. The demand for oil is inelastic. As a rule of thumb, for every +/-10% demand, the oil price will +/- $75 in price[9]. The same is true for supply.

Russia is currently engaged in a war with Ukraine. In retaliation, the US and a coalition of Western allies have imposed and array of financial sanctions on the Russian economy. Russia currently exports about 5 million barrels/day of oil into international markets. In retaliation for the sanctions, Russia could immediately halt some or all of its exports and cause a further spike in the price of oil. Some banks have forecast this scenario could raise oil prices to $380/barrel.

This scenario may seem improbable, but consider Putin’s logic for doing so:

· A price spike would make the cost of living so high that many incumbent governments in Europe would probably fall. Their replacements would probably have a more restrained foreign policy, shattering the West’s coalition against Russia. Additionally, Putin knows a price spike close to the November midterm elections in the US would harm Biden and the Democrats, who lead the sanctions regime globally.

· A partial export restriction would raise the price of oil and partially pay for itself.

· Russia is desperate, so they may be crazy enough to do this. The country is in late-stage demographic decline and their military is too small to defend their current borders.

· The US will likely ramp up shale production in 2023, so Putin knows he has a limited window to use his weapon.

· Putin’s graduate school thesis was about using Russia’s resources for geopolitical ends, so he’s thought about this.

There are many reasons for Russia NOT to do this, but the probability of Putin deploying the oil weapon is not zero and history demonstrates it’s been done before. If this were to occur, the price of gasoline would further increase (see Figure 8) and inflation would spike.

Figure 8: What goes into the price of gasoline

To mitigate this risk, the US should take its destiny into its own hands and dramatically increase domestic oil and gas production. Doing so would decrease inflation and the price at the pump.

[1] Wall Street Journal

[2] Energy Information Administration (EIA)

[3] EIA

[4] https://priusblack.blogspot.com/2016/10/clean-rooms.html

[5] EIA

[6] Financial Times

[7] EIA

[8] Mirsky, Rich (June–July 2005). "Trekking Through That Valley of Death—The Defense Production Act". Innovation. Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

[9] Zeihan, Peter. The End of the World Is Just the Beginning: Mapping the Collapse of Globalization. Harper Business, 2022.

Outstanding article! I am looking forward to reading the future ones.