Legacy of the Great Recession

Part 2 of the American economy series focuses on the lingering effects of the 2008 Great Recession

Tl;dr

· We still feel the legacy of the 2008 Great Recession today

· The crisis was caused by a US housing bubble

· The Federal Reserve responded to the crisis in unprecedented ways, including dropping interest rates to zero for a decade and deploying several rounds of quantitative easing

· The 2010s were starkly different for those with and without assets

· The long-term effects of the Great Recession include inequality, a distorted stock market, deglobalization, and schizophrenic politics

SUBSCRIBE HERE

American history is a series of pivots that influence everything that happens until the next pivot. The shadow each pivot casts may be decades long. The US Civil War led to the battles over Reconstruction until the Spanish-American War ignited a debate over US imperial ambitions in the world. The Great Depression grew the size and scope of the federal government until Pearl Harbor drew the country into a world war. And 9/11 launched a Global War on Terror until the Great Recession focused our attention back on a hollowed-out homeland.

These pivots are often only apparent in hindsight. I, for one, was oblivious as the global financial system imploded. I was a senior in high school and a freshman in college in 2008. The Kansas Jayhawks football team went to the Orange Bowl and the basketball team won a national championship, influencing my decision to attend the University of Kansas in the fall of 2008. As a freshman fraternity pledge, one of my duties was to deliver newspapers like The Wall Street Journal to upperclassmen. I remember seeing headlines like "Lehman folds with record $613 billion debt" and "U.S. Expands Plan to Buy Banks' Troubled Assets" but I was definitely more interested in girls and partying.

But in hindsight, the Great Recession deeply influenced the last 15 years and its legacy permanently scars the US economy today.

Overview of the Crisis

The 18-month-long contraction of gross domestic product (GDP) known as the Great Recession was the longest since the Great Depression (43 months) in 1929.[i] The origins and anatomy of the economic contraction are complex and this post is focused on its lingering effects, so this overview will be high level. If you are interested in more detail, I recommend The Big Short, Meltdown, or Crashed.

In the 1990s and 2000s, financial firms began to issue “subprime mortgages”. Subprime mortgages went to individuals deemed to be of low creditworthiness who in the past, may not have been eligible for a mortgage. As this became very profitable, more and more subprime mortgages were issued. In the mid-990s, 1 in 20 mortgages were subprime; by 2006 1 in 4 were[ii]. At the same time, financial firms bundled up individual mortgages into Mortgage-backed Securities (MBS) and traded them amongst a global network of banks.

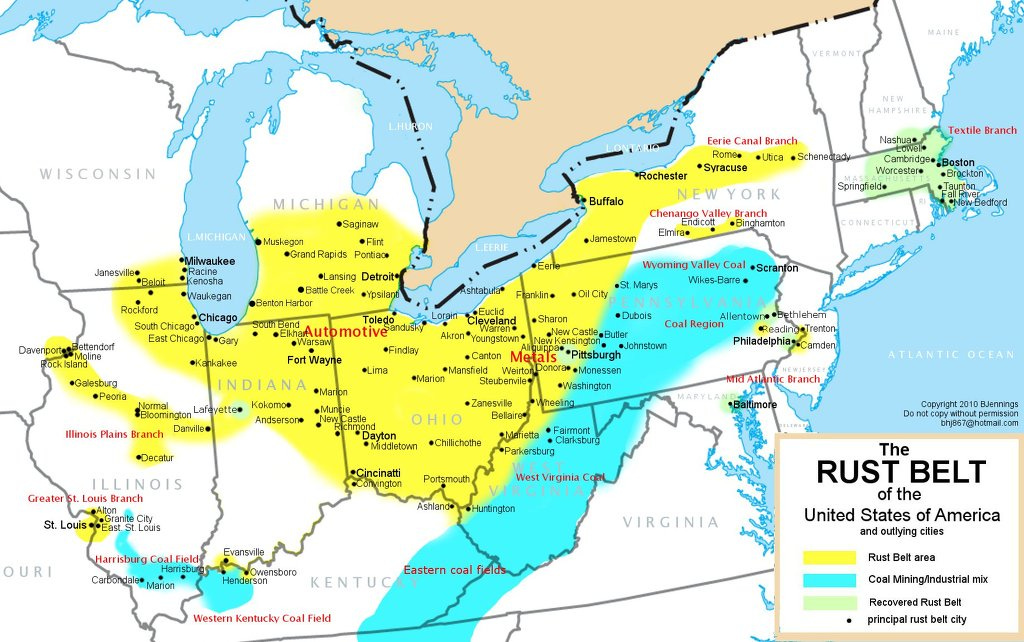

Some of the mortgagors began to default in economically depressed areas hit hard by deindustrialization in the American Rust Belt[iii]. These defaults spread as housing prices declined nationwide and the value of the MBS began to decline. The MBS were constructed so that even if only a small percentage of the mortgages defaulted, the value of the whole security declined substantially. Since these MBS made up a large portion of bank assets globally, what followed was a 21st century version of an old-fashioned bank run. Banks around the world began to fail in what is now known as the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Figure 1: The geography of the Rust Belt

Credit markets seized up and economic activity on “Main Street” decreased as individuals and firms could not get loans. Governments stepped in to bailout the banks, but it was too late. The Great Recession had begun.

The Fed’s Response

I outlined the Fed’s role in the economy in the Introduction to this series, but as a reminder it is responsible for controlling the money supply in the US economy. Congress gave the Fed a dual mandate: to maintain price stability (control inflation) and maximize employment. Inflation wasn’t an issue in 2008 but layoffs spiked dramatically and the unemployment rate rose from 4.4% to 10.1%[iv]. The Fed took unprecedented steps to prop up the economy.

The Fed has two primary ways to throttle the economy: interest rates and quantitative easing. Following the crisis, the Fed dropped interest rates to near zero and left them there for nearly a decade. In theory, this was designed to stimulate the economy by incentivizing lending and investment. In practice, it incentivized companies to buy back their stock with cheap loans and hurt normal people who relied upon savings accounts to build their wealth (with 0% interest rates, accounts didn’t accrue interest).

Figure 2: Federal Reserve interest rates[v]

Quantitative easing (QE) is a euphemism for printing money. At the time, it was a novel way for the Fed to increase the money supply. When the government spends more than it receives in tax revenue, it issues bonds to cover the shortfall. Investors buy the bonds, which will pay interest over time, and give the government cash to immediately pay for its spending. With QE, the Fed bought the government’s bonds and paid for them by creating money in the government’s account: with a few keystrokes, the Fed digitally printed trillions of dollars. The theory of QE was that stimulating demand for bonds would keep the price high. The price of a bond is inversely related to its interest rate and QE was meant to keep long-term interest rates low, thereby stimulating the economy. Confused? That’s OK, it didn’t really work and massively distorted the economy.

Figure 3: QE explained...sort of

Before it was done, there were three rounds of QE ending in 2015. The Fed printed $3.9 trillion[vi], a 4x expansion of their balance sheet from before the crisis. Defenders of QE will say it prevented a New Great Depression but we’ll never know that counter-factual. What we do know is the reality of the last 15 years, which has seen a massive gap open between the haves and the have-nots.

A Tale of Two Cities: The 2010s

For the owners of assets, particularly stocks, the past decade has been the roaring-10s. Those who owned tech-disruptors like the FAANGs (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google) have done extremely well, with their value increasing by more than 1000% from the Great Recession. That is because easy money policy from the Fed has inflated their valuations.

Figure 4: Asset bubbles since 1977[vii]

For everyone else (which was many people since only 53% of people own stocks[viii]), the last decade has not been as roaring. The unemployment rate spiked to 10.1% at the onset of the Great Recession and didn’t return to pre-recession levels until 2018. Fed zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) was intended to promote job growth by allowing firms to invest in productive capacity using cheap loans. Instead, they used those cheap loans to buy back their stock, prompting a “jobless recovery”.

Figure 5: Unemployment after the Great Recession[ix]

The housing market stayed very unhealthy for several years. At the peak of the crisis, 4 million homes were foreclosed and 2.5 million businesses were closed each year[x]. The reach of these foreclosures was nationwide. The scars from these economic wounds feature prominently on the American economy today.

Figure 6: Housing foreclosures in 2012[xi]

Long-term Legacy of the Great Recession 1: Wealth Inequality

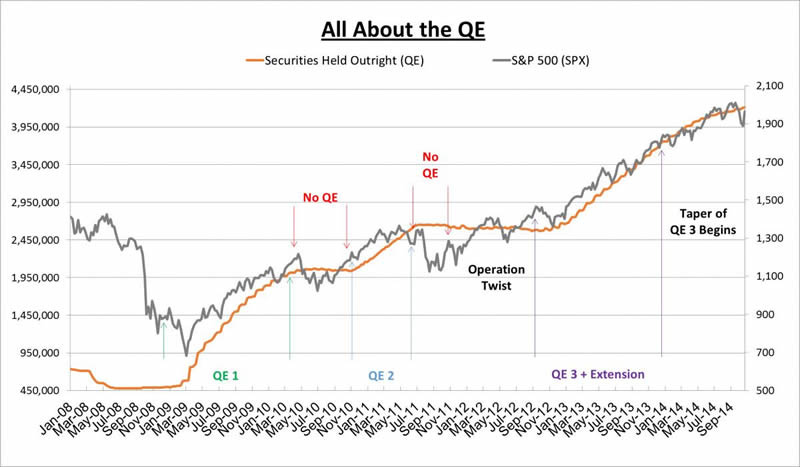

As the Fed dropped interest rates and printed money (QE), the stock market boomed. In fact, as Figure 7 shows there is a direct correlation between the deployment of QE and the rise of the stock market.

Figure 7: QE and the stock market correlated[xii]

Those who owned stocks benefited massively. The top 1% added more than $20 trillion in wealth while the bottom 50% added nothing. At present, inequality in the US is at levels not seen since the Great Depression. Throughout history and across societies, when wealth distribution is not seen as fair, great internal frictions tend to arise.

Figure 8: Inequality after the Great Recession[xiii]

Long-term Legacy of the Great Recession 2: Distorted Stock Market

A company can artificially influence its share price by buying back its own stock off the market. For example, let’s say a hypothetical company is trading at $10/share with 100 shares of its stock outstanding. Its market value is $1000 ($10/share x 100 shares). It decides to buy back 10 shares at the market rate of $10/share, so there are now only 90 shares outstanding. But the company’s value is still $1000, so the value of all outstanding shares goes to $11.11 ($1000 / 90 shares). Everybody who owned stock in that company just got richer but the company produced no new economic value.

This kind of financial engineering became very popular in the wake of the Great Recession as the Fed deployed ZIRP for a decade. As interest rates were dropped to near 0%, the theory was that companies would take out cheap loans to hire people or invest in productive equipment. Instead, companies took out loans to buy back their stock. Between 2010 and 2019, companies bought back $3.5 trillion in stock. This money was not used to create jobs or innovate in the real economy, and instead enriched the owners of stocks further exacerbating inequality.

Figure 9: Stock buybacks after the Great Recession[xiv]

Long-term Legacy of the Great Recession 3: Deglobalization

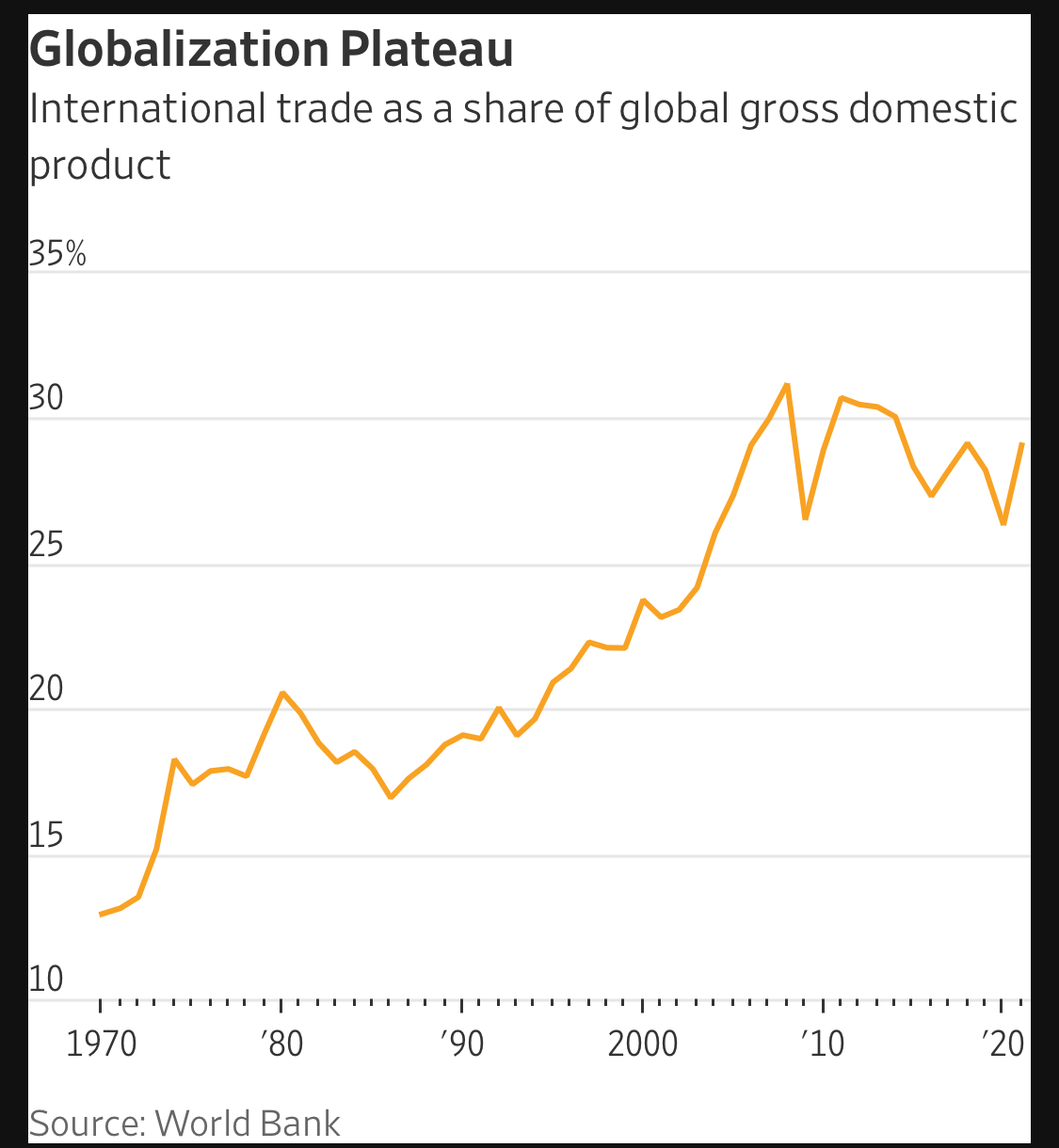

One of the major trends of the post-WW2 world was globalization. While there were local losers, as a whole globalization ushered in the most economically prosperous and peaceful era in history. Millions were lifted out of poverty around the world. And thanks to global supply chains, the price of most goods dropped for Americans. That all ended with the Great Recession. Since 2008, international trade has stagnated. Some argue that globalization had gone too far, harming workers in developed countries. Others counter that deglobalization will lead to higher prices and a more dangerous world. It’s too soon to know which side is right, but the backlash to globalization is the defining political debate of our time. The only certainty is that globalization stalled after the Great Recession.

Figure 10:Stagnation of international trade[xv]

Long-term Legacy of the Great Recession 4: Impact on Politics

The banks had failed and the stock market had crashed, sweeping a populist president easily to power. The year was 1932 and the President was Franklin D. Roosevelt. Eerily similar conditions brought President Barack Obama to power in 2008. FDR closed the banks, passed banking reform bill called Glass-Steagall Act that was 53 pages long[xvi], and indicted several Wall Street executives for fraud in public hearings[xvii]. Though the ensuing Great Depression (it had already started when he came into power) was difficult, the banker-bashing brought catharsis to the nation and created a Democratic coalition that lasts to this day.

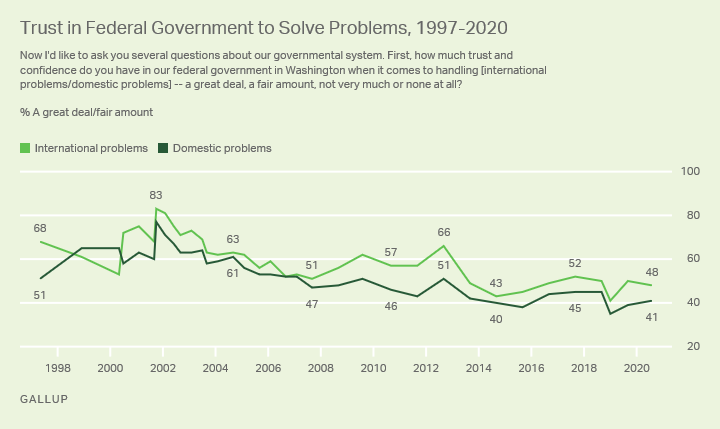

Figure 11: Protests outside the US Supreme Court

In contrast, the Obama Administration bailed out the Too Big To Fail banks, indicted zero Wall Street executives for fraud, and passed a 3,500+ page[xviii] Dodd-Frank banking reform act written by Wall Street lobbyists. Defenders of the Administration will say that they prevented a New Great Depression, and they may be right. In fact, the Chairmen of the Fed at the time, Ben Bernake, was a leading scholar of the Great Depression and based many of his actions on that research. But we’ll never know and there was certainly no catharsis. Instead, political debate about the federal response began almost immediately and its legacy underlies our political discourse to this day. In every election since 2008, Americans have voted for change and polls show they have gradually lost trust in the federal government.

Figure 12: American's trust in the federal government to sole problem[xix]

Up Next

Thanks for reading the Legacy of the Great Recession in this multipart series on the American economy. Up next is Deindustrialization and its Effects.

SUBSCRIBE HERE

[i] https://www.ocregister.com/2018/09/17/4-charts-show-how-bad-the-great-recession-was-10-years-ago/

[ii] Moss, D. (2011). Fighting a dangerous financial fire: the federal response to the crisis of 2007-2009. HBS No. 9-711-104. Harvard Business School Publishing.

[iii] Klein, Matthew C., and Michael Pettis. Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace, with a New Preface. Yale University Press, 2021.

[iv] BLS

[v] New York Times

[vi] CNN

[vii] Bank of America

[viii] https://usafacts.org/articles/what-percentage-of-americans-own-stock/

[ix] BLS

[x] https://www.ocregister.com/2018/09/17/4-charts-show-how-bad-the-great-recession-was-10-years-ago/

[xi] RealtyTrac

[xii] https://www.marketoracle.co.uk/images/2014/Nov/stocks-qe.jpg

[xiii] New York Times

[xiv] S&P CapialIQ

[xv] Wall Street Journal

[xvi] https://archive.org/details/FullTextTheGlass-steagallActA.k.a.TheBankingActOf1933/page/n51/mode/2up

[xvii] https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/were-bankers-jailed-in-past-financial-crises/

[xviii] https://www.compliancebuilding.com/2011/05/03/the-monstrous-size-of-dodd-frank/

[xix] Gallup