Sunday Digest #1

Economic Strength and Military Power, Using the Korean Model to End the Ukraine War?, Regulating AI, Global Immigration, the Fourth Turning

Welcome to the first edition of the Sunday Digest, a weekly newsletter from Ad Astra. In this digest, I’ll include excerpts from five articles from the week along with my commentary and analysis. This digest will be a bit long and can be split up throughout the week, quickly scanned, ignored, or read in one sitting. Let’s begin.

When it comes to the economy, size doesn’t always matter

Military strength isn’t always correlated with GDP

It’s a commonly held belief that military strength is directly correlated with economic size. If that’s the case, the USA ($23 trillion[i] GDP) is stronger than China ($18 trillion[ii] GDP) and far stronger than Russia ($2 trillion[iii]GDP). But is that true for an economy that’s 70%+ services like the USA (hotels, restaurants, and iPhones made in China)? China is the world’s manufacturer and Russia is outproducing the USA by 3:1[iv] in artillery shells. US artillery shell production has not been able to keep up with Ukrainian demand during the war. The ammo shortage is so severe for the West that the USA is sending Ukraine cluster munitions, weapons banned by most allies and a move even newspapers friendly to the Biden Administration have criticized.

A recent article by Policy Tensor on Substack analyzes the relationship between GDP and military strength:

The idea that the economic size and industrial development of the powers was the decisive conditioner of war-making capabilities emerged from World War I. The dominance of firepower over mobility meant that wars would be wars of attrition fought along long, static fronts where prodigious quantities of munitions would be expended until one side capitulated. Unlike agrarian societies of similar demographic size, big industrial countries could field armies of several million men; armies that were voracious consumers of munitions, industrially manufactured war material, food and other supplies. Such massive armies could therefore be fielded for any appreciable length of time only by countries of great economic size and industrial strength.

…on the Eastern Front the social scientific theory of war is unpersuasive, for the mobilized GDP ratios favored the Germans during the decisive phase of the Soviet-German war, 1941-1943. Harrison’s own data show that, as late as 1943, the ratio of Soviet to German mobilized GDP was 1.1, as was the ratio of raw GDP.

So, how did the Reds do it? Simple: the Soviets simply produced more weapons than the Germans. Even though the ratio of mobilized GDP was 1.1 in favor of the Germans, the ratio of weapons production was 1.5 in favor of the Soviets! (Both of these tables are from my “Western Perceptions of Soviet Strength in the Soviet-German War,” which was based on archival work in the O.S.S. archives under Adam Tooze’s supervision.)

The problem with the GDP fetish is that what really matters in protracted great power wars of attrition is not economic size per se, but defense-industrial production capacity. GDP serves as a good proxy only in as much as it captures variation in the latter. The position of your analyst is that, instead of using proxies like GDP, we need to directly interrogate the defense-industrial base. What does that say about the present balance of underlying war-making capabilities?

fielded for any appreciable length of time only by countries of great economic size and industrial strength.

Essentially, wars of attrition tested the capacity of the great powers to sustain the war effort for longer than their adversaries.

Electricity generation is a useful proxy of industrial scale. China surpassed the US around 2010. It now produces twice as much electricity as the United States.

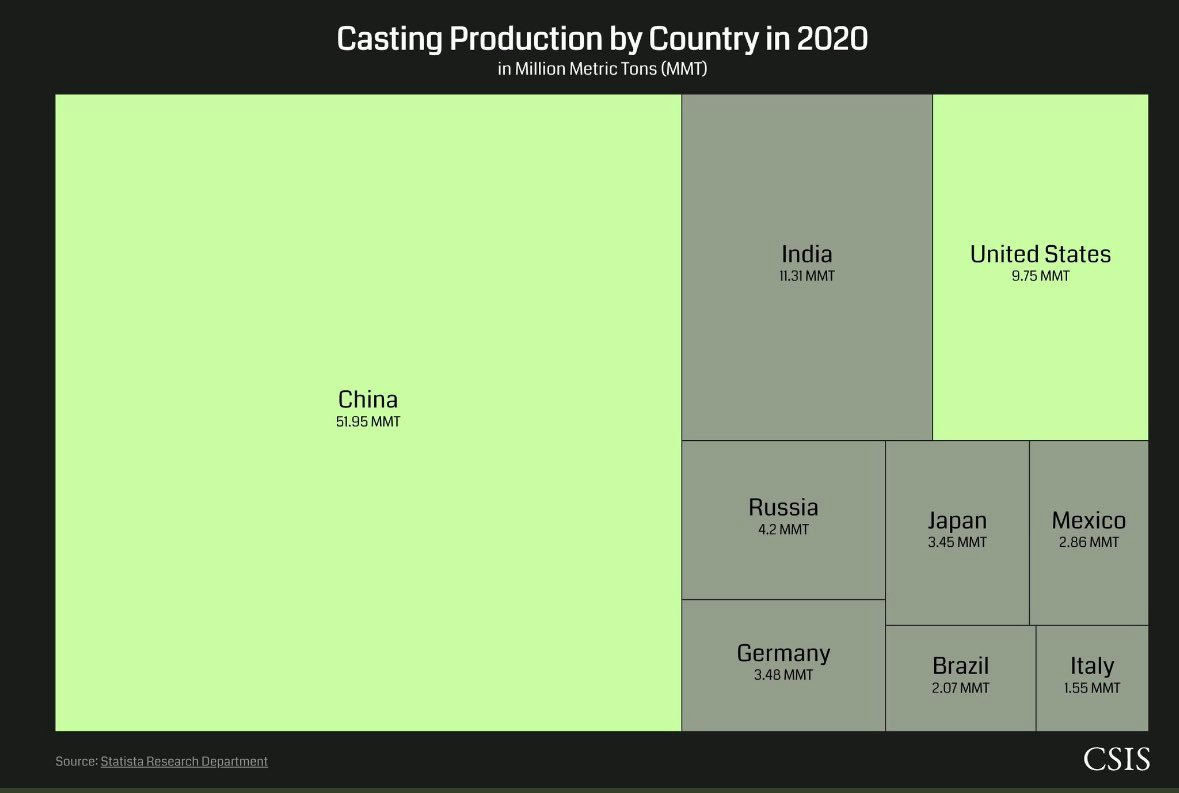

In Ukraine, we’ve seen how sustaining production of basic materials can be challenging. Specifically, there’s been a running crisis over the production of artillery shells. Even though every war since World War I has been, first and foremost, an artillery war, the tendency of Congress and the Services is to focus on sexy and expensive weapons systems to the neglect of basic capabilities. Now, the underlying capacity that is relevant to all such capabilities is the scale of casting production. China’s casting production in 2020 was five times as large as that of the United States’s. I’m greatly worried that the United States has let its defense-industrial base deteriorate while China’s has been growing in leaps and bounds.

The obvious solution to all this is to ramp up our defense-industrial base. But according to the AP, that will take 5 years and still be insufficient for Ukraine’s needs:

The Army is spending about $1.5 billion to ramp up production of 155 mm rounds from 14,000 a month before Russia invaded Ukraine to over 85,000 a month by 2028, U.S. Army Undersecretary Gabe Camarillo told a symposium last month. “Already, the U.S. military has given Ukraine more than 1.5 million rounds of 155 mm ammunition, according to Army figures. “But even with higher near-term production rates, the U.S. cannot replenish its stockpile or catch up to the usage pace in Ukraine, where officials estimate that the Ukrainian military is firing 6,000 to 8,000 shells per day. In other words, two days’ worth of shells fired by Ukraine equates to the United States’ monthly pre-war production figure.[v]

Assuming conservatively that Ukraine uses 6,000 artillery shells per day, that’s 180,000 shells per month or more than 2x what the US plans to produce in 2028. That is pathetic. WW2 lasted four years and the US mobilized to provide enough equipment to supply itself and its allies around the world. The Pentagon was built in sixteen months. As previously mentioned on this Substack, it now takes longer on average to get an environmental permit (five years) than the total time it took— from start to finish—to build the Hoover Dam. We must place a priority on rebuilding our defense industrial base.

I’ve said before that the USA has all the cards geopolitically and that our great power rivals China and Russia face headwinds. But a card player can misplay even a lucky hand.

End the Ukrainian War using the Korea Model

Last fall, Ad Astra called for a cease fire in Ukraine; 8 months later, our position is the same

After 500 days, the war in Ukraine is presently in a stalemate. The long-awaited Ukrainian counteroffensive hasn’t made any progress to date. Time is on Russia’s side as 1) they have a huge population advantage (4x), 2) they’re firing 20,000 artillery shells/day (50,000 on peak days) vs. 6,000-8,000 shells/day for Ukraine[vi], and 3) the USA is out of ammo to supply Ukraine. Putin, Biden, and Zelensky’s political survival are all tied to battlefield success, making the situation extremely dangerous. The only thing to gain from further war is death and more favorable terms for Russia. Meanwhile, China wants the war to continue so the USA is distracted. A longer war is a win for China.

Despite the huge human cost of the war, the USA has been the big winner so far:

The Americans have managed to:

1. sever Europe from Russia economically and politically

2. re-orientate the EU’s economy toward the USA

3. make the EU reliant on US energy exports by denying it Russian oil and gas

4. reduce European states to little more than American satrapies, with European Prime Ministers/Premiers little more than local branch office managers

5. embarrass Russia on the global stage with its failure to deliver a swift knockout blow in Ukraine

6. expand US arms exports[vii]

The latest issue of Foreign Affairs provides a model for peace based on the 1950s proxy war on the Korean Peninsula. That ceasefire gave us modern North and South Korea, which are formally still at war. In 1952, Chinese diplomats began to broach the subject of an armistice with Stalin:

The fighting would rage for another ten months before the two sides would agree to an armistice…Ultimately, 36,574 Americans were killed in the war and 103,284 were wounded. China lost an estimated one million people, and four million Koreans perished—ten percent of the peninsula’s population.

The armistice ended that bloodshed, establishing a demilitarized zone and mechanisms to supervise compliance and mediate violations. But the Korean War did not officially conclude. The major political issues could not be settled, and skirmishes, raids, artillery shelling, and occasional battles broke out. They never escalated to full-blown war, however. The armistice held—and 70 years later, it still holds.

The war ravaging Ukraine today bears more than a passing resemblance to the Korean War. And for anyone wondering about how it might end, the durability of the Korean armistice—and the high human cost of the delay in reaching it—deserves close study. The parallels are clear. In Ukraine, as in Korea seven decades ago, a static battlefront and intractable political differences call for a cease-fire that would pause the violence while putting off thorny political issues for another day. The Korean armistice “enabled South Korea to flourish under American security guarantees and protection,” the historian Stephen Kotkin has pointed out. “If a similar armistice allowed Ukraine—or even just 80 percent of the country—to flourish in a similar way,” he argues, “that would be a victory in the war.”[viii]

How to Regulate AI

In our post on AI, we emphasized the lack of consensus on how to regulate AI. ChatGPT, the popular app that introduced AI to the masses, is still only eight months old. Sam Altman, the CEO of ChatGPT-maker OpenAI, testified in front of Congress in May asking to be regulated. Skeptics noted this was likely a bid to entrench OpenAI’s lead in the AI arms race by imposing regulatory burdens on OpenAI’s competitors. By creating regulatory steps, like requiring individual models to be given a license from the government (like the FDA approves drugs), competitors will be slowed down and open-source models will not exist. In this regulatory environment, politically-connected or heavily-resourced firms would be advantaged, likely ensuring that existing Big Tech firms win the AI race.

Jeremy Howard, a founding researcher at fast.ai and an honorary professor at the University of Queensland, published a report on the potential unintended consequences of mis-regulating AI:

Artificial Intelligence is moving fast, and we don’t know what might turn out to be possible. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman thinks AI might “capture the light cone of all future value in the universe”. But things might go wrong, with some experts warning of “the risk of extinction from AI”.

This had led many to propose an approach to regulating AI, including the whitepaper “Frontier AI Regulation: Managing Emerging Risks to Public Safety” (which we’ll refer to as “FAR”), and in the Parliament version of the EU AI Act, that goes as follows:

Create standards for development and deployment of AI models, and

Create mechanisms to ensure compliance with these standards.

Other experts, however, counter that “There is so much attention flooded onto x-risk (existential risk)… that it ‘takes the air out of more pressing issues’ and insidiously puts social pressure on researchers focused on other current risks.”

Important as current risks are, does the threat of human extinction mean we should go ahead with this kind of regulation anyway?

Perhaps not. As we’ll see, if AI turns out to be powerful enough to be a catastrophic threat, the proposal may not actually help. In fact it could make things much worse, by creating a power imbalance so severe that it leads to the destruction of society. These concerns apply to all regulations that try to ensure the models themselves (“development”) are safe, rather than just how they’re used. The effects of these regulations may turn out to be impossible to undo, and therefore we should be extremely careful before we legislate them.

The kinds of model development that FAR and the AI Act aim to regulate are “foundation models” — general-purpose AI which can handle (to varying degrees of success) nearly any problem you throw at them. There is no way to ensure that any general-purpose device (like, say, a computer, or a pen) can’t ever be used to cause harm. Therefore, the only way to ensure that AI models can’t be misused is to ensure that no one can use them directly. Instead, they must be limited to a tightly controlled narrow service interface (like ChatGPT, an interface to GPT-4).

But those with full access to AI models (such as those inside the companies that host the service) have enormous advantages over those limited to “safe” interfaces. If AI becomes extremely powerful, then full access to models will be critical to those who need to remain competitive, as well as to those who wish to cause harm. They can simply train their own models from scratch, or exfiltrate existing ones through blackmail, bribery, or theft. This could lead to a society where only groups with the massive resources to train foundation models, or the moral disregard to steal them, have access to humanity’s most powerful technology. These groups could become more powerful than any state. Historically, large power differentials have led to violence and subservience of whole societies.

If we regulate now in a way that increases centralisation of power in the name of “safety”, we risk rolling back the gains made from the Age of Enlightenment, and instead entering a new age: the Age of Dislightenment. Instead, we could maintain the Enlightenment ideas of openness and trust, such as by supporting open-source model development. Open source has enabled huge technological progress through broad participation and sharing. Perhaps open AI models could do the same. Broad participation could allow more people with a wider variety of expertise to help identify and counter threats, thus increasing overall safety — as we’ve previously seen in fields like cyber-security.

There are interventions we can make now, including the regulation of “high-risk applications” proposed in the EU AI Act. By regulating applications we focus on real harms and can make those most responsible directly liable. Another useful approach in the AI Act is to regulate disclosure, to ensure that those using models have the information they need to use them appropriately.

AI impacts are complex, and as such there is unlikely to be any one panacea. We will not truly understand the impacts of advanced AI until we create it. Therefore we should not be in a rush to regulate this technology, and should be careful to avoid a cure which is worse than the disease.

Global Immigration and the Populist Backlash

Immigration is a big political issue in the US and around the world. The rise of anti-establishment, populist political parties globally is a backlash to increasing global migration. Since history tells us that political unrest often happen in global waves (see the Age of Revolution, 1848 revolutions, and decolonization after WW2), this issue is important to understand. The New York Times did a good piece explaining the big picture:

The global migration wave of the 21st century has little precedent. In much of North America, Europe and Oceania, the share of population that is foreign-born is at or near its highest level on record.

In the U.S., that share is approaching the previous high of 15 percent, reached in 1890. In some other countries, the immigration increases have been even steeper in the past two decades:

This scale of immigration tends to be unpopular with residents of the arrival countries. Illegal immigration is especially unpopular because it feeds a sense that a country’s laws don’t matter. But large amounts of legal immigration also bother many voters. Lower-income and blue-collar workers often worry that their wages will decline because employers suddenly have a larger, cheaper labor pool from which to hire.

As Tom Fairless, a Wall Street Journal reporter, wrote a few days ago:

Record immigration to affluent countries is sparking bigger backlashes across the world, boosting populist parties and putting pressure on governments to tighten policies to stem the migration wave.

The backlashes repeat a long cycle in immigration policy, experts say. Businesses constantly lobby for more liberal immigration laws because that reduces their labor costs and boosts profits. They draw support from pro-business politicians on the right and pro-integration leaders on the left, leading to immigration policies that are more liberal than the average voter wants.

Personally, I thing dramatic changes in communication technology (discussed here, here, and here) have more to do with the success of anti-establishment, populist parties but immigration certainly plays a part.

The Fourth Turning

Finally, we end this digest on an apocalyptic note with a cyclical theory of history that has entered the popular culture: the Fourth Turning. A sense of impending doom is widespread.

The New York Times did a piece summarizing the ominous prophecy:

Close watchers of “The Watcher,” the popular Netflix series about a couple who move to the New Jersey suburbs, only to be stalked in their dream home, may have caught the reference.

It comes when one of the main characters, played by Bobby Cannavale, stumbles upon a creepy man in his kitchen who describes himself as a building inspector. After Mr. Cannavale’s character remarks that people are fleeing New York City, the man replies: “It’s the fourth turning.”

The puzzlement on Mr. Cannavale’s face invites an explanation.

According to “fourth turning” proponents, American history goes through recurring cycles. Each one, which lasts about 80 to 100 years, consists of four generation-long seasons, or “turnings.” The winter season is a time of upheaval and reconstruction — a fourth turning.

The theory first appeared in “The Fourth Turning,” a work of pop political science that has had a cult following more or less since it was published in 1997. In the last few years of political turmoil, the book and its ideas have bubbled into the mainstream.

According to “The Fourth Turning,” previous crisis periods include the American Revolution, the Civil War and World War II. America entered its latest fourth turning in the mid-2000s. It will culminate in a crisis sometime in the 2020s — i.e., now.

One of the book’s authors, Neil Howe, 71, has become a frequent podcast guest. A follow-up, “The Fourth Turning Is Here,” comes out this month.

The book’s outlook on the near future has made it appealing to macro traders and crypto enthusiasts, and it is frequently cited on the podcasts “Macro Voices,” “Wealthion” and “On the Margin.”

“I’ve read ‘The Fourth Turning,’ and indeed found it useful from a macroeconomic investing perspective,” Lyn Alden, 35, an investment analyst, wrote in an email. “History doesn’t repeat, but it kind of gives us a loose framework to work with.”

For Ryen W. Thomas, 42, a filmmaker and co-host of a YouTube series, “Generational Talk,” “The Fourth Turning” captured a mood of decline in recent American life. “I remember feeling safe in the ’90s, and then as soon as 9/11 hit, the world went topsy-turvy,” he said. “Every time my cohort got to the point where we were optimistic, another crisis happened. When I read the book, I was like, ‘That makes sense.’”

It could be true? Best to stock-up on bottled water and ramen noodles.

One media recommendation:

There you have it, the first edition on Sunday Digest with stories about preparation for war, war, rapid technological change, destabilized politics, and a popular theory to tie it all together. The portrait of a world spinning faster and faster. The good news is you have Netflix, Uber Eats, and running water. Until next time, be a good citizen, quit doomscrolling, and go outside.

Ad Astra Per Aspera!

[i] World Bank

[ii] World Bank

[iii] World Bank

https://twitter.com/davidsacks/status/1678463164864667658?s=42&t=nVb-5uC_WM3Cp0R0dGiqHQ

[v] AP

https://twitter.com/davidsacks/status/1678463164864667658?s=42&t=nVb-5uC_WM3Cp0R0dGiqHQ

[vii] https://substack.com/inbox/post/134475794

[viii] https://reader.foreignaffairs.com/2023/06/20/the-korea-model/content.html

![A DEMOCRAT AT THE BORDER?! RFK Jr. Visits Southern Border, Calls Crisis 'Unsustainable' [WATCH] A DEMOCRAT AT THE BORDER?! RFK Jr. Visits Southern Border, Calls Crisis 'Unsustainable' [WATCH]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!TgKa!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F749f77d6-a2c8-4056-877c-062570ebf71a_540x960.jpeg)