Figure 1: A Google protester dressed as Mr. Monopoly

Antagonism towards monopolies, especially Big Tech, is one of the few issues on which present day Democrats and Republicans agree. Brought by the Trump Administration and being argued by the Biden DOJ, the United States v. Google is the largest monopoly lawsuit since Microsoft in the 1990s and early 2000s. At issue is the default placement of Google search engines on devices like the iPhone, a privilege for which Google pays Apple billions. Google claims its search engine is simply the best, while critics say its only the best because of scale…which it gets through default placement.

Ad Astra covered the monopoly issue in Welcome to the New Gilded Age and specifically discussed the unique dangers posed by Big Tech. I increasingly find myself using ChatGPT for things I would have searched for in the past due to its superior answers and the proliferation of “sponsored” results on Google search. But even if search is about to be disrupted by AI, the US v. Google will set an important precedent for how or if Big Tech is addressed. The New York Times covers the dimensions of this trial:

Americans have long been skeptical of big business. Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Harry Truman all tried to constrain the power of large companies. Their efforts were part of a national culture that long emphasized individual freedom.

In the 1960s, however, a group of scholars began arguing that large corporations had been unfairly maligned. These scholars — led by Robert Bork, then an obscure law professor — made the case that big business was often efficient and innovative. And if a large company did try to take advantage of consumers, these scholars said, a competitor could swoop in and lure away those consumers.

For years, Bork and his allies failed to persuade Washington to embrace their views. But after the U.S. economy struggled during the 1970s, policymakers became worried that antitrust laws were keeping American companies from competing with Japanese and European rivals. Slowly, the Bork view won converts, among both Republicans and Democrats. Since the 1980s, that view has dominated, allowing corporations to grow much larger.

That history is a crucial backdrop to the Google antitrust trial that began this week.

Google certainly looks like a monopoly by many measures. More than 90 percent of web searches worldwide are done on Google.

This level of dominance can create problems for anybody who isn’t a Google executive or shareholder. The company is so profitable that it can shape government policies through lobbying and donations. Google can potentially hold down wages for anybody who wants to work in internet search: Where else is that person going to go? Google can also essentially force consumers to turn over their personal data to the company; to exist in today’s economy, you need to interact with Google’s various services, like search, Gmail, Google Cloud and YouTube.

“For the past decade, Google and other tech giants have become incredibly powerful and entwined in just about every aspect of our lives,” Cecilia Kang, one of the Times reporters covering the Google trial, told me.

The Justice Department’s case against the company (and a related lawsuit brought by 38 states and territories) argues that Google has unfairly maintained its dominance by paying other companies billions of dollars a year. Payments to Apple, for example, are the reason that Google is the default search engine on iPhones. As a result, the Justice Department says, competitors to Google cannot establish themselves.

Google responds that its success is simply a reflection of the quality of its products. “People don’t use Google because they have to,” Kent Walker, Google’s top lawyer, has written. “They use it because they want to.”

The government’s biggest challenge in winning this case is closely connected to Bork’s framework for antitrust policy. He argued that the most rigorous standard for judging potential monopolies was consumer prices. Only when economic analysis proved that a company was so powerful that it could raise consumer prices should regulators step in, Bork and his allies said. Otherwise, the government was just guessing about when a company was so big as to be problematic.

Google, of course, charges consumers nothing for its main products. The company makes money in other ways, such as advertisements. The same dynamic exists elsewhere in the technology industry. Facebook does not charge consumers for an account, either. Amazon does charge for products on its site, but often not any more than other retailers.

In recent years, a rising generation of legal scholars has tried to overturn the Bork consensus by arguing that large companies can still do damage even without increasing prices. They can hold down wages, warp government policy, trample on privacy or spread misinformation.

(One member of this rising generation is Lina Khan, whom President Biden named to run the Federal Trade Commission.)

As part of their argument, these critics of big business — the intellectual heirs to Theodore Roosevelt — can point to macroeconomic data. In the four decades since Bork’s view triumphed, wages for most Americans have grown more slowly than either corporate profits or the incomes of the wealthy. Corporate consolidation seems to have been better for a small slice of privileged people, including Google executives, than for most Americans.

In the long term, these critics hope to change the legal standard for evaluating large companies, much as Bork and other scholars slowly did in the late 20th century. Doing so will probably require new laws as well as different attitudes among regulators and judges. Such a project might take decades, if it ever succeeds.

In the meantime, the Justice Department’s lawyers hope to persuade Amit Mehta, the federal judge hearing the case, that Google hasn’t violated even the lenient antitrust laws of today.

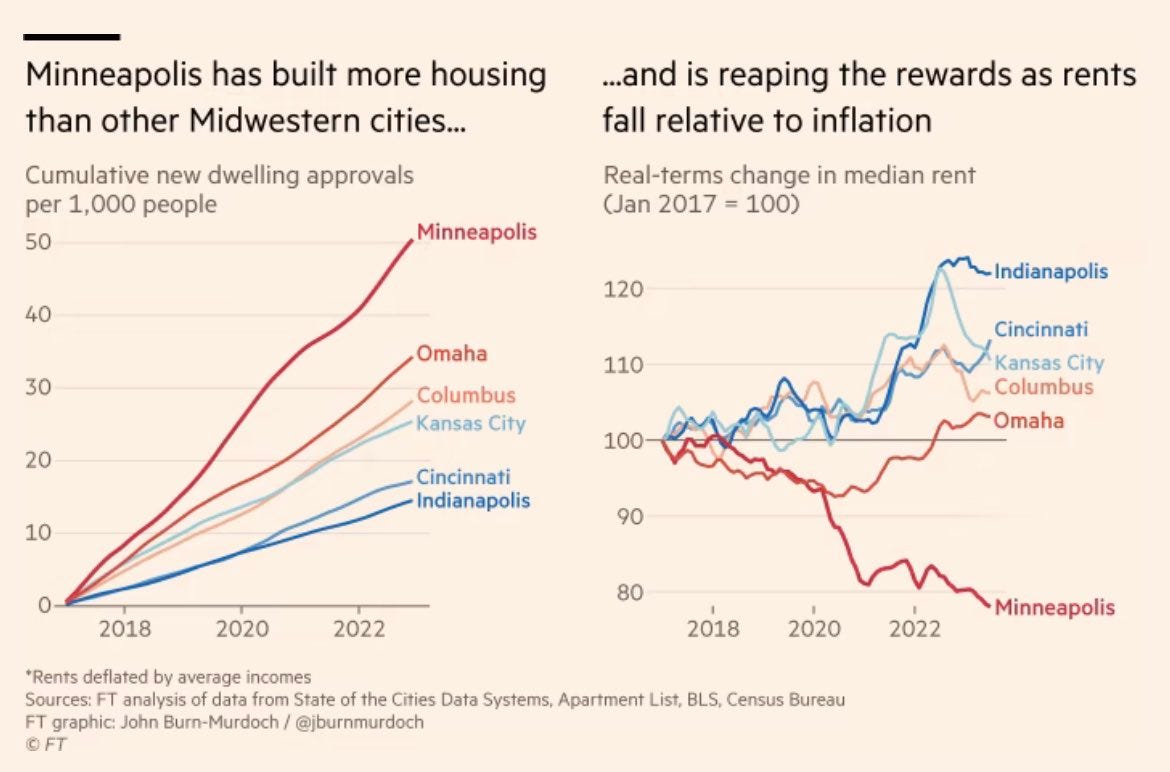

Interesting chart

Housing prices, both to rent and buy, are out of control across America. Minneapolis has figured out the solution is simply to build more houses.

Media recommendation

This week, I recommend the Substack of the 86-yeaar-old journalist Seymour (Sy) Hersh. Sy came to prominence during the Vietnam-era and won the 1970 Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on the Mai Lai massacre. His reporting on the war in Ukraine has been excellent.

There you have it, the tenth edition of Sunday Digest featuring Big Tech on trial, why the rent is too damn high, and a legendary Vietnam-era journalist reinvented for the Ukraine-era. The portrait of a world spinning faster and faster. The good news is you have Netflix, Uber Eats, and running water. Until next time, be a good citizen, quit doomscrolling, and go outside.

Ad Astra Per Aspera!