If you watch the news, you’ll be convinced that the US is on the brink of civil war. If you walk the streets of San Francisco, you’ll be struck by how marvelous technological advances can be next to stark inequality. I believe the latter framing is the correct way to understand modern America.

In the 19th century, America went through the Industrial Revolution which upended society and how politics were organized – a period we call the Gilded Age. In the 20th century, the Information Revolution has once again upended society. The First Gilded Age led to the reforms of the Progressive Age in the 1900s. The Second Gilded Age today is going to lead us…somewhere.

Mark Twain once said “history doesn’t repeat but it rhymes”. It would be misinterpreting history to say that what happened once will happen again, but there are lessons to be learned from studying the past. The Council on Foreign Relations put out an interesting article comparing today to the 1890s:

The most popular historical analogy for current American troubles is the Civil War era. The second most popular is the Gilded Age. But where the 1850s do not meaningfully resemble today, the 1890s certainly do. Technological change, economic concentration, and rising inequality; political partisanship, financial corruption, and social turmoil;

the similarities are striking. Moreover, the paths the country took out of that earlier crisis offer valuable lessons for what we should do now, and what we should fear.

In the last third of the nineteenth century, the United States was a country in ferment due to three broad trends: economic growth and industrialization, demographic growth and social change, and the rise of mass political participation. These national transformations fed on one another, as did the backlashes they provoked.

From 1870 to 1900, the U.S. population doubled from 38 million to 76 million, and by the turn of the century, one in seven Americans was a new immigrant. The population spread across the continent as railroads, steamships, telegraphs, and telephones tied the country together and linked it to the world at large. In the South, meanwhile, the democratizing thrust of Reconstruction increasingly brought formerly enslaved people into the mainstream of regional life.

The combination of modern corporations, industrial research labs, and globalized markets kicked off an unprecedented surge of continuous technological innovation and economic growth. And as usual with capitalist development, all that was solid melted into air. As economic historian Brad DeLong puts it, “Before 1870, you almost certainly had a job very much like that of your father or mother. After 1870, that was no longer the case. A wild ride of Schumpeterian creative destruction gave rise to enormous wealth while destroying entire occupations, livelihoods, industries, sectors, and communities.” The historian Henry Adams claimed that “the American boy of 1854 stood nearer the year 1 than to the year 1900.”

The rhythms of the business cycle battered the old middle classes both ways. Booms eroded traditional social structures and hierarchies, while busts left individuals stranded and bereft. Agricultural employment plummeted and the industrial workforce became proletarianized, even as economic consolidation produced huge organizations and giant fortunes at the top of the ladder. “Small shops employing artisans or skilled workers increasingly gave way to larger mechanized factories using more unskilled labor,” writes the historian Charles W. Calhoun in The Gilded Age: Perspectives on the Origins of Modern America. “American workers found their economic lives reduced from independence to dependence as the wage system of labor came to dominate the workplace.”

Throughout the turmoil, two equally strong patronage-based national parties fought each other to a draw as electoral politics became mass entertainment and a major seasonal jobs program. Historian Jon Grinspan captures the scene in The Age of Acrimony: How Americans Fought to Fix Their Democracy, 1865–1915:

Presidential elections drew the highest turnouts ever reached, were decided by the closest margins, and witnessed the most political violence.…The nation experienced one impeachment, two presidential elections “won” by the loser of the popular vote, and three presidential assassinations. Control of Congress rocketed back and forth, but neither party seemed capable of tackling the systemic issues disrupting Americans’ lives. Driving it all, a tribal partisanship captivated the public, folding racial, ethnic, and religious identities into two warring hosts….Republicans tended to support an active federal government, while Democrats denounced “centralism,” but mostly, each side just opposed what the other stood for.

As the mainstream parties let problems fester, the disaffected started taking matters into their own hands and organizing for resistance. Angry farmers and miners joined the Grange, the Greenback and Union Labor parties, and the Populists. Angry industrial workers joined the Knights of Labor, the American Federation of Labor, and the American Railway Union. And angry moralistic reformers joined the mugwumps, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and the progressives. By the last decade of the century, the nation was starting to boil.

The Gilded Age’s dynamism and instability triggered economic, communal, and political backlashes, which over time coalesced to produce a semblance of order. Economic populists started to rein in laissez-faire, slowly establishing checks on some aspects of business activity. And progressive reformers gentrified the political system, reducing mass participation and introducing technocracy. Together, these moves led to what would become known as the Progressive Era.

There are clearly many parallels between then and now. Both the late nineteenth and the early twenty-first centuries saw technological change, increased globalization, economic growth, concentration of wealth, and rising inequality. Karl Marx described the way steam, railroads, and the telegraph had shrunk the world as the annihilation of space by time; in recent decades, the information revolution and digital technology have shrunk the world still further, producing similar vertigo.

Both witnessed the growth of an increasingly raucous and demotic public sphere, first in the nation’s streets and now on its information superhighways. And both featured national alarms over substance abuse and terrorism(alcohol and anarchism in the nineteenth century, opioids and Islamic fundamentalist terrorism in the twenty-first).

One lesson the case teaches, therefore, is that certain kinds of reforms can make life better. The sustained economic growth that began in the late nineteenth century has continued ever since, generating astonishing material progress, but the problems of the late nineteenth century have remained as well. Free markets produce vast wealth but distribute their benefits irregularly and unevenly while causing constant social destabilization. The only way capitalism and democracy can peacefully coexist, therefore, is for policymakers in each new era to find ways to sustain economic growth while ensuring society as a whole shares in the benefits.

The most basic lesson from the Gilded Age and its aftermath is thus one about democratic agency. External or structural force can present problems for the country, but citizens choose how to respond. As the Wisconsin Progressive Robert La Follette insisted, “America is not made. It is in the making.” In the end, therefore, the question is not what kind of country we are. It is what kind of country we want to be.

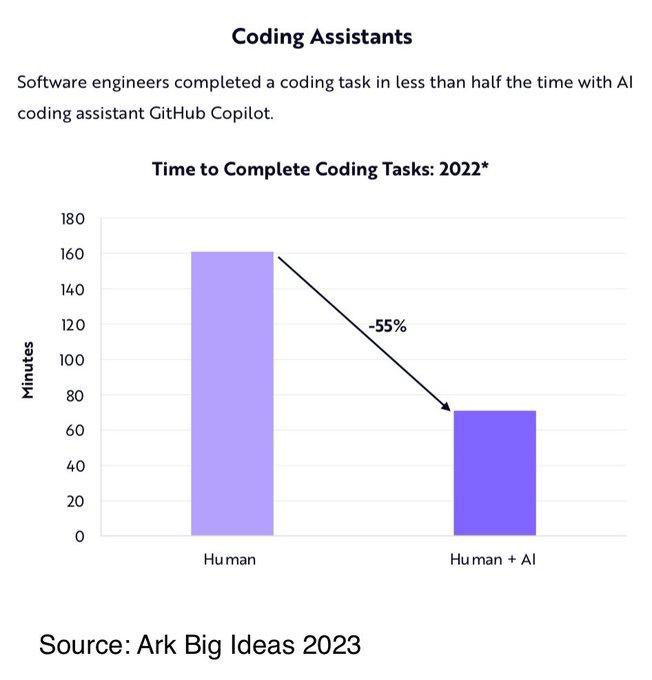

One interesting chart

Innovations in AI have led to massive productivity gains for coders. This will lead to layoffs in tech or significant expansion of tech into more traditional industries.

Media recommendation

One historian has come up what he claims is a scientific method for analyzing society. His conclusion? We are living in the End Times.

There you have it, the fourth edition of Sunday Digest with a story comparing the Gilded Age to today, the bleak future for human coders, and a pseudo-scientific prognostication of the apocalypse. The portrait of a world spinning faster and faster. The good news is you have Netflix, Uber Eats, and running water. Until next time, be a good citizen, quit doomscrolling, and go outside.

Ad Astra Per Aspera!