Sunday Digest #5

The New Scramble for Africa

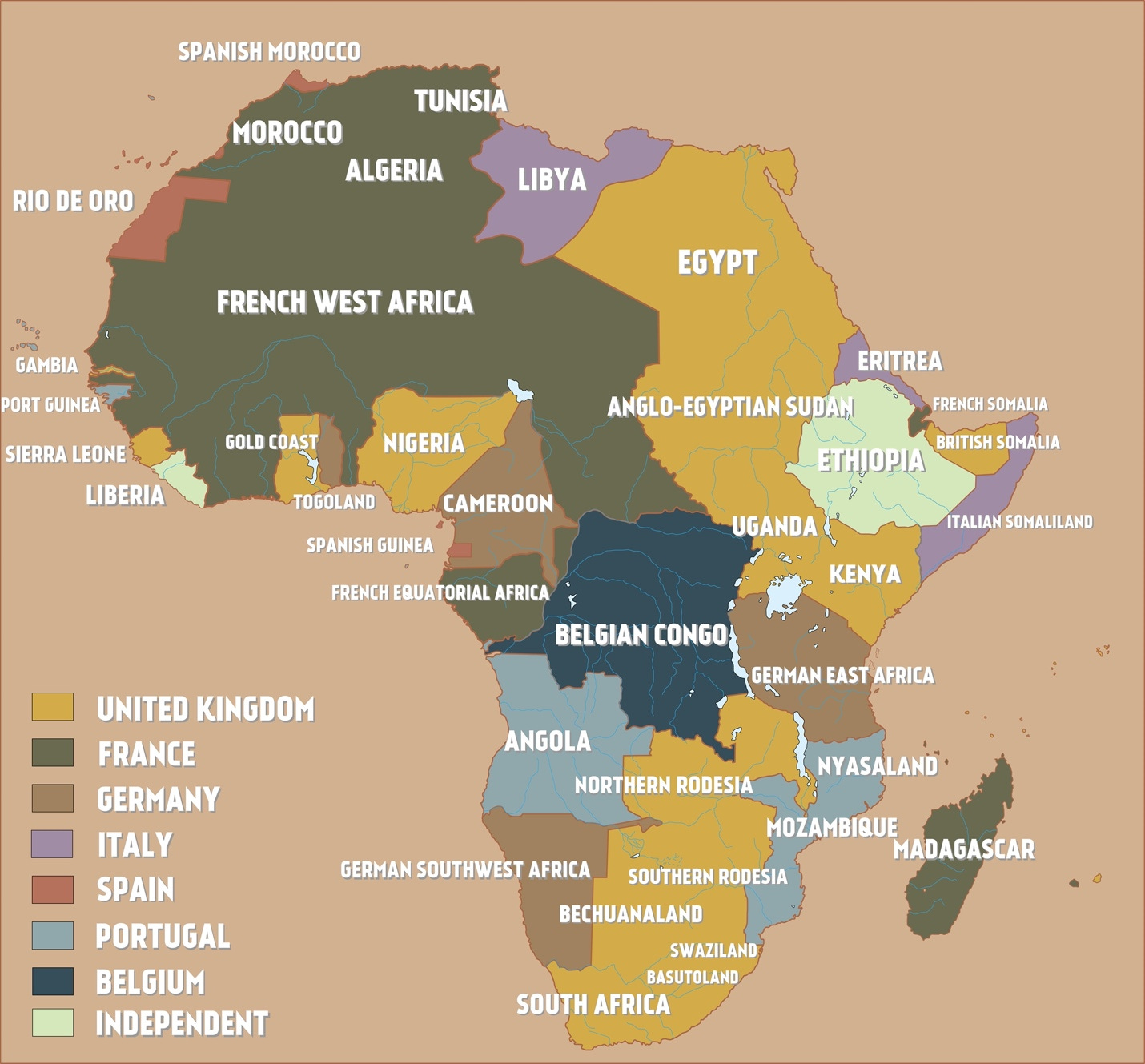

Figure 1: Colonial Africa (1914)

The “Scramble for Africa” was the late-19th century colonization of Africa by the imperial European powers (like Britain, France, and Germany). The powers were competing for resources, territory, and influence. In the 21stcentury, there’s a New Scramble for Africa led by the likes of China and Russia. Though old-fashioned imperialism has gone out of style, the control of resources like oil and rare earth minerals has not.

The West has largely set this race out, fearing anything that may be construed as colonialism. Contemporary Western academia has been very critical of colonialism. This critique is based in reality, but has been taken too far. Unburdened with the historical legacy of colonialism, China and Russia have had no problem spreading their influence in Africa.

In recent weeks there was a coup in Niger, with the military overthrowing the democratically-elected government. There has been a stand-off between the democratic world and the military junta to restore the elected president. In response, the coup leaders have enlisted the help of Russia-backed Wagner mercenaries. Wagner has been implicated in supporting recent coups in neighboring Mali and Burkina Faso.

Der Spiegel has a new piece titled “China and Russia Are Beating the West in Africa” exploring the 21st century geopolitical ramifications of the New Scramble for Africa:

nearly all major powers are showing a huge interest in Africa…The continent, once largely perceived as a trouble spot, is now increasingly seen as a strategic partner.

Moscow is sending Wagner mercenaries to, among other countries, Mali, where they are propping up the junta, to the dismay of former colonial power France. The European Union and the United States have launched a charm offensive on the continent to avoid losing more countries to Russia and China.

Raw materials from Africa – oil and gas, but also lithium and cobalt – are becoming increasingly important. Heads of state and companies from around the world are lining up in countries like Senegal, Congo and Namibia. China, Turkey and now Europe are trying to build up influence in Africa through infrastructure projects. Some are speaking of a new "scramble for Africa" – a reference to the colonial conquests in the 19th and 20th centuries and the bloc politics of the Cold War.

But one thing is different now – the African countries are now self-confident. They can choose their partners and are doing so. It matters who makes the best offer: Russia, China, the U.S., the EU – in many cases, it's less a question of ideology than of cost-benefit calculations.

The Europeans don't seem to have found an answer yet to this shift, having for decades primarily seen Africa as a boogieman full of potential migrants. The new race for Africa is a global power shift – with an open outcome.

Material of the Future

The ceiling tiles in Manono's community hall are rotten. There is a crack in the concrete floor. There is no electricity, so the organizers have set up a generator outside, which powers the speaker and microphone inside. But most participants at this event don't need microphones, they are voicing their concerns loudly. In Manono's "Grande Salle," in southeastern Congo, the issue at hand is global geopolitics. It is about who will have access to the metal of the future: "The Chinese" or "the ones from the West." The residents of Manono and the employees of the Australian mining company AVZ Minerals have gathered here. The company, which wants to mine lithium, set up the meeting.

Lithium is one of the most sought-after raw materials in the world, and experts believe that demand will far exceed supply. Lithium is used in battery production and is necessary for the transition to green energies. Geologists believe that the world's largest lithium deposit could lie under Manono, untapped. "Manono can play a significant role in meeting the world's demand for lithium," says Nigel Ferguson, the CEO of AVZ Minerals. Some believe that whoever controls Manono might have a say in the prices on the global markets.

Africa is full of raw materials that the rest of the world depends on – lithium, cobalt but also gold and diamonds. The world' largest deposit of platinum is also on the continent. Ever since the revival of nuclear energy in many places, uranium is once again in demand, and eyes are turning especially to Namibia and Niger, which are home to large deposits. In short, the global north's industrial growth wouldn't be possible without Africa.

The Australians found large amounts of lithium-rich rock in Manono in 2018. Because it's expensive to mine the metal, they teamed up with another company, in which the Chinese battery giant CATL has a stake. For $240 million, the Chinese were promised a 24-percent stake in the Dathcom joint lithium venture. "We would have loved to have worked with European or American companies, but unfortunately, they're afraid of investing in countries like Congo," says AVZ head Ferguson.

Europe and the U.S. are afraid of losing influence in Africa. But nobody wants to invest large amounts of money in an instable country. According to experts, most of Congo's raw materials exports go to China. "Chinese President Xi Jinping has issued the directive: Go out and get what you can. And now we're experiencing exactly that," says Ferguson.

The war in Ukraine and the end of Russian gas exports to Europe has led to the hunt for new supplies in Africa:

A large deposit of the fossil fuel [gas] was discovered under the seabed in 2015 on the border between Senegal and Mauritania. Since then, the two countries have been working together to produce it and are hoping to derive billions in revenue. The natural gas is to be extracted for at least 30 years, with the profits shared by energy giants BP and Kosmos together with Senegalese and Mauritanian state-owned companies.

Thierno Seydou Ly…The general director of Petrosen, the state oil and gas company, speaks in an interview in a hotel in the capital of Dakar. It's important to him that his message is understood, so he expresses himself in a calm manner. "Gas is an enormous opportunity for our country," he says, "also because there is a huge need for new producers as a result of the war in Ukraine." Senegal is thus trying to fast track its way to becoming a gas nation. Processes that normally take years need to be completed in months. "At the moment, everyone is knocking on our door," says Ly.

A fossil-fuel boom has broken out in many African countries. In Uganda, the French company Total wants to extract oil in a nature preserve together with a Chinese state company. There are plans for a pipeline that can transport the oil through the Tanzanian Serengeti to the Indian Ocean. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, oil fields are being auctioned off to the highest bidders. Drilling is also taking place off the southern coast of Namibia, where several platforms are already installed in the water, even though the country is presenting itself as a trailblazer in the green energy revolution. Countries are taking what they can.

Many projects are still in the early stages, but hopes on the continent are high, as is the interest of oil and gas corporations from industrialized nations. In 2021, the African countries altogether produced 260 billion cubic meters of gas. According to the Forum of Gas Exporting Countries, that volume is expected to rise to as much as 585 billion cubic meters by 2050.

The Changing of the Guard

A few months before his biggest victory thus far, the lawyer and activist Drissa Meminta steps up to a lectern in a courtyard in Bamako, the capital of Mali. He's wearing a dark-blue suit with a breast pocket handkerchief. Around him, in a semi-circle, his fellow members of the anti-colonial, pro-Russian Yerewolo movement have gathered for an internal meeting. A banner displays their goal in the national colors: "The liberation of Mali."

Meminta recalls what his movement has achieved so far. It helped bring the military junta to power in 2021, which helped spur the withdrawal of the French military one year later. Now, he wants the United Nations peacekeepers to leave the country as well. "It has to be the aspiration of every country to take its fate into its own hands," says Meminta.

As it turns out, the UN declared a short time later that their MINUSMA peace mission would come to an end this year.

the stabilization of Mali proved impossible. Ever larger parts of the country fell under the de facto control of the jihadists. Elements of the military carried out a coup against the government in 2020 and 2021.

What is happening in Mali is tantamount to a changing of the guard: The Europeans are leaving; with the Russians arriving in their place. Up to 1,600 mercenaries belonging to the Wagner Group are already stationed in Mali, and their influence is growing.

Long before the Wagner militia, led by Yevgeny Prigozhin, waged war in Ukraine, it served as an instrument with which the Kremlin could expand its influence in Africa. Wagner mercenaries are supporting the warlord Khalifa Haftar in Libya. In Sudan, they run gold mines together with the warlord Hemeti. The Wagner network is active in at least a dozen African countries. No other state has as many bilateral agreements with governments on the continent as Russia. And no other country sells more weapons to sub-Saharan Africa.

The Russian government recently announced plans to compensate African countries for the loss of Ukrainian wheat

Moscow is spreading the propaganda that it is the former colonial powers, like France, who are exploiting the continent, while the Russians themselves are aiming for a more equal partnership.

In the Central African Republic, for instance, the Wagner mercenaries have succeeded in infiltrating part of the state following the French retreat. Experts speak of a "state capture." They reportedly looted raw materials like gold and timber.

For many African despots, the Wagner mercenaries, whose "engagement" in Africa continues regardless of their boss Yevgeny Prigozhin’s mutiny, are a convenient partner. They help them face down political opponents and insurgents and they receive access to raw materials in return. Unlike the Europeans, they don’t ask questions about democracy or human rights.

An Unequal Race

In Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s seat of government, the past and the future are never far apart. There’s the old train station, built by the Germans when the region was their colony, with its battered red roof shingles. Next to it, a modern glass building rises into the sky, the new train station built by a Turkish company.

Masanja Kadogosa is standing on the platform, which is still empty, and looking contentedly into the distance. "Moving traffic from road to rail will improve people’s lives in Tanzania," he says.

As the director of Tanzania Railways, Kadogosa is overseeing what is currently one of Africa's largest infrastructure projects. The Tanzania Standard Gauge Railway, or SGR, will connect Tanzania with Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi and Congo. Ten billion dollars have been earmarked for investment in the project. The route will be built by Turkish and Chinese companies. The Tanzanian clients have changed partners several times to get a better deal. "It’s our choice who we work with," says Kadagosa. "We know exactly what we want. And that has also made us more picky."

The SGR is a symbol of the new balance of power on the continent. Just over three decades ago, more than eight out of 10 construction contracts in Africa went to American or European firms. Ten years ago, it was still around one out of three, but by 2020, it will only be around one in 10. Chinese companies now implement one-third of all infrastructure projects.

Whether it's the Turks in Tanzania, the Russians in Mali or the Chinese in the Democratic Republic of Congo, African countries are reorienting themselves. One reason is that, for years, the West wasn’t very interested in Africa politically.

the Chinese pulled past Western countries to take the lead in Africa. From 2000 to 2020, Chinese financiers lent $160 billion to African governments, two-thirds of which flowed into infrastructure projects. In recent years, Beijing has relied more on direct investment and trade than lending.

But Russia's war against Ukraine, the systemic competition between China and the U.S. and the increased demand for raw materials as countries transition to clean energies is all leading to a rethink in the West. Africa is suddenly perceived as a "geopolitical marketplace," as EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell recently put it.

One interesting chart

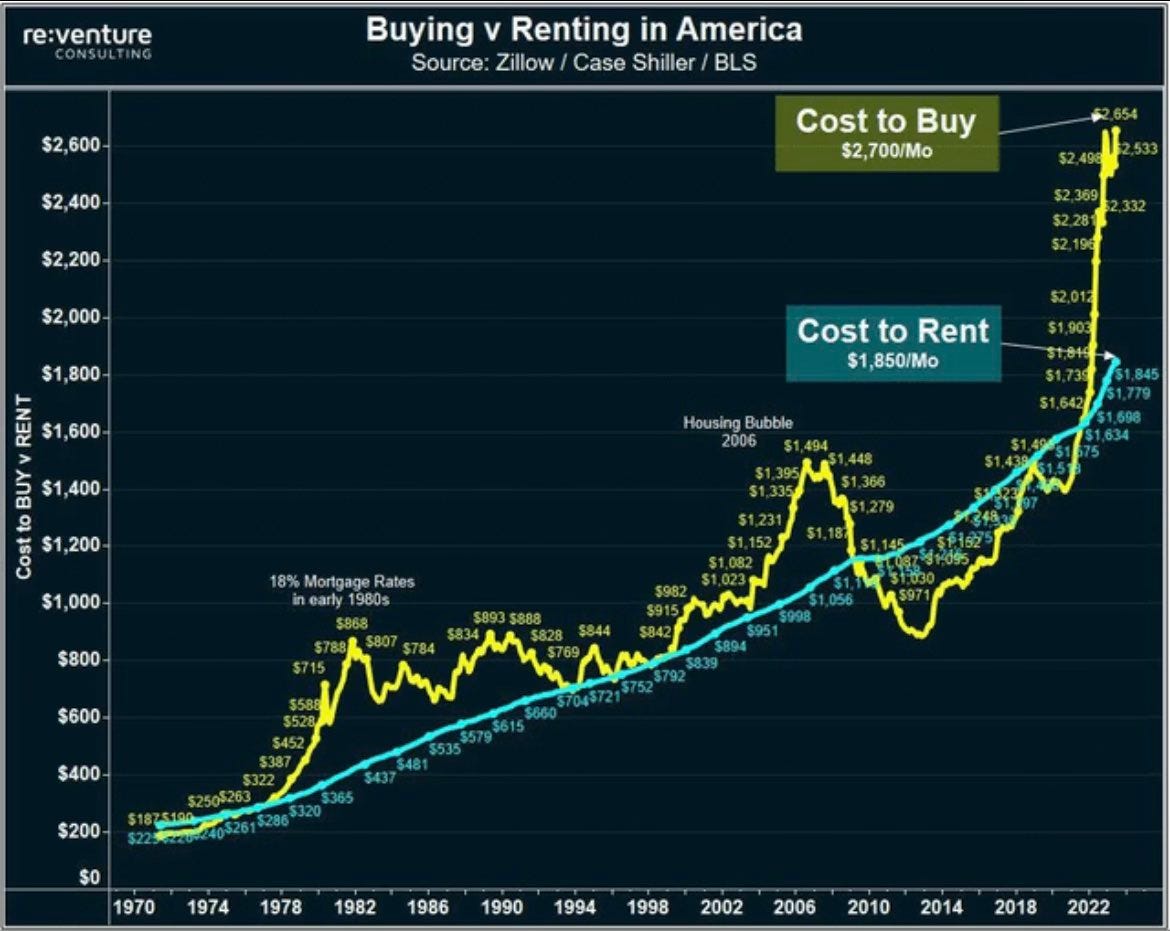

Buying a house in America has gotten significantly more expensive recently due rapid Federal Reserve interest rate hikes, which have made monthly mortgage rate payments higher. This has caused the cost of buying to greatly exceed the cost of renting an equivalent home. This is bad news for non-homeowners, as buying a home is the one of the most common ways to grow wealth in America.

Media recommendation

Fitting with the theme of this week’s digest, the rise of the rest, here is a podcast on the end of the dollar as the world’s prime reserve currency. While I don’t fully buy into the gloomiest de-dollarization forecasts, its food for thought.

There you have it, the fifth edition of Sunday Digest with a New Scramble for Africa, unaffordable housing, and the end of the dollar. The portrait of a world spinning faster and faster. The good news is you have Netflix, Uber Eats, and running water. Until next time, be a good citizen, quit doomscrolling, and go outside.

Ad Astra Per Aspera!