Earlier this week Ad Astra wrote abouts the BRICS summit in South Africa and the rise of a multipolar word order. Pundits squabble about the prospects of the BRICS organization, but there can be no doubt about the rise of a multipolar world order and its intent to decrease use of the dollar. This is the most important change happening in the world today beyond America’s borders. Viewed through this lens, much of the conflict between establishment political factions, who promote policies from America’s era of singular dominance, and populist challengers can be explained.

The Financial Times calls this the à la carte world:

For a telling insight into the seismic changes reshaping the global order, it is worth a glance at the official schedule of Kenya’s diplomats. There was a time when they were called upon to host delegations from global powers relatively rarely. No longer. Now there is barely a slot free in their calendar.

In the early summer Nairobi hosted in quick succession US officials to discuss a free trade deal, Russia’s foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, to address parliament, and EU officials to sign a trade agreement.

Kenya’s military commanders have an impressively full dance card too: in May, for example, an Indian frigate anchored off Mombasa for a joint naval exercise, even as British Royal Marines trained Kenya’s first commando unit.

All the while China, which two decades ago identified Kenya as a vital partner in Africa, in its then fledgling courtship of the continent, is investing in infrastructure leading from the Indian Ocean coast to the interior. China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, popped by in July. Oh yes, and Iran’s president Ebrahim Raisi had a red-carpet reception in Kenya in July at the start of an African tour.

Welcome to the à la carte world. As the post-cold war age of America as a sole superpower fades, the old era when countries had to choose from a prix fixe menu of alliances is shifting into a more fluid order.

The stand-off between Washington and Beijing, and the west’s effective abandonment of its three-decade dream that the gospel of free markets would lead to a more liberal version of the Chinese Communist party, are presenting an opportunity for much of the world: not just to be wooed but also to play one off against the other — and many are doing this with alacrity and increasing skill.

One senior western policymaker, privy to thinking in the west and China, sees it as a “once-in-a-generation shift”. Western diplomats talk of the era of “fence-sitters” and “swing states”. For Ivan Krastev, the political scientist, it is the age of the middle powers. The word “middle”, he stresses, refers to their position — in between the US and China — rather than their weighting.

His vision encompasses a range of distinctly un-middling countries including traditional US allies such as Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Israel and even Germany, as well as titans of the global south, such as Indonesia and India, patently a rising great power.

Beyond the Brics

This new less regimented landscape most obviously benefits the global south, the loose term broadly synonymous with the developing economies of Latin America, Africa and Asia. Their heightened ambitions will be on display in South Africa in mid-August at the summit of the Brics nations, Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

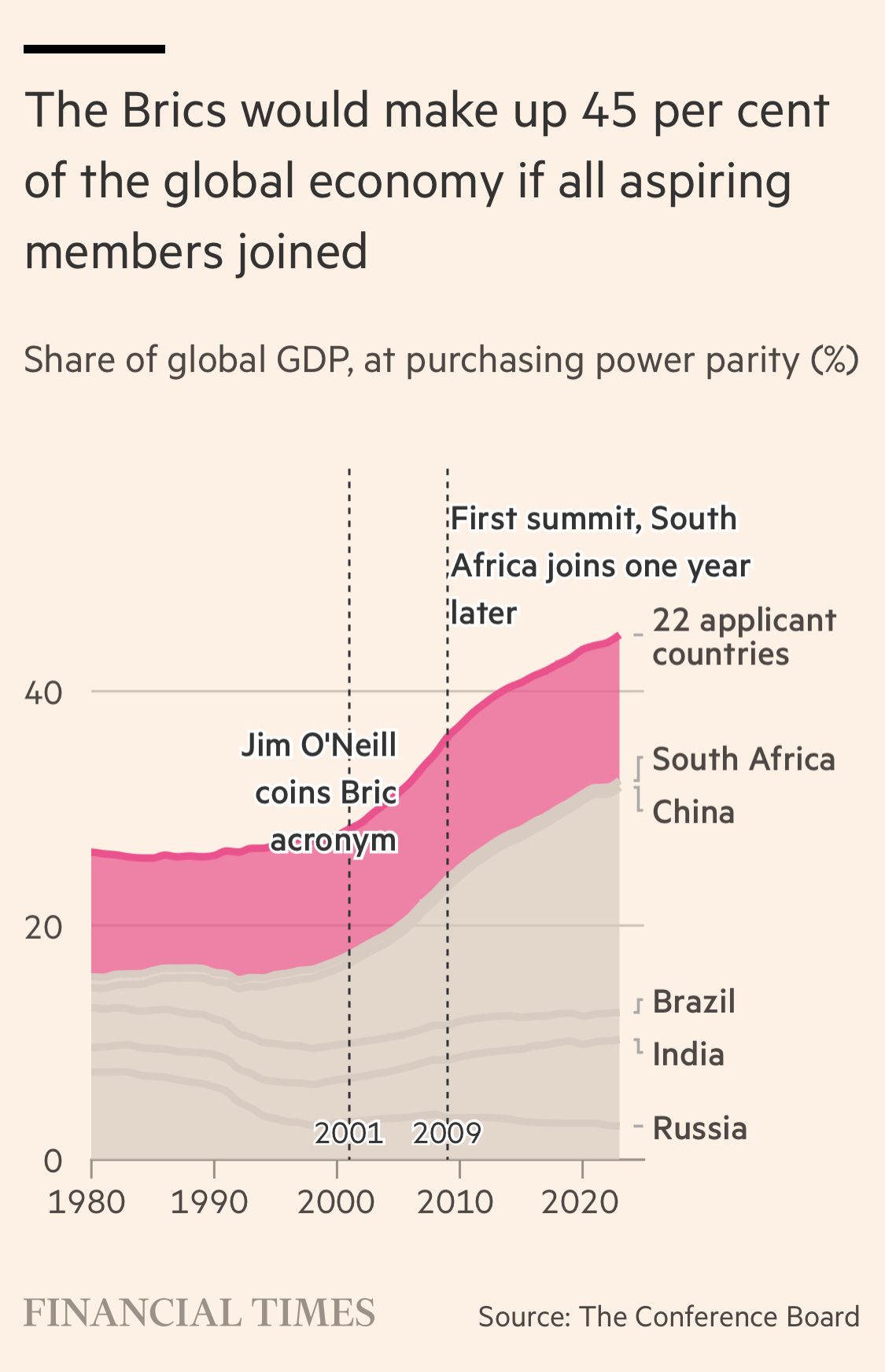

The Brics was formalised in the aftermath of the financial crisis drawing on a classic jazzy bankers’ acronym — it was coined by Goldman Sachs economists — when their interests were more aligned than now. The founding four later invited South Africa, a relative economic minnow, to join; its inclusion brought Africa into the group.

Now after some years treading water, the Brics is gathering momentum. Symbolically at least the summit has the potential for being seen as the 21st-century equivalent of the Bandung conference of 1955, which launched the non-aligned movement.

Top of the agenda is the application of 22 countries to join, and which if any to accept. The eclectic roll call of suitors includes global south ideological stalwarts such as Venezuela and Vietnam, but also Middle East actors such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iran, and powerhouses from other regions, including Indonesia, Nigeria and Mexico.

Add all of them, and the block would represent 45 per cent of the global economy. Even a more limited expansion would create a behemoth accounting for almost half the world’s population and 35 per cent of its economy, says Anil Sooklal, South Africa’s ambassador to the Brics who is co-ordinating the summit. He anticipates “a more ambitious agenda and more forceful position, including a strong push for reform of the global political, economic and financial architecture”.

In its stance over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Turkey is a case study of a country choosing sometimes to align itself with the west and sometimes to stand against it. Its unpredictability was to the fore this summer at the Nato summit when it did a U-turn in allowing Sweden to join the alliance.

Western officials see Saudi Arabia and the UAE very much in this category of states behaving more assertively on the global stage and more independently of their traditional ally, America. Policymakers in Brussels have noted their intensified engagement in the politics of the Horn of Africa, for example, and also of course Saudi Arabia’s hosting of Ukrainian peace talks, and concluded that the EU needs to rethink its foreign policy priorities and focus. “We need to be engaging more with such countries,” says a senior EU official. “A large part of our foreign policy structures are 20 years out of date.”

De-dollar diplomacy

And yet for all the discordance behind the scenes in Johannesburg, most of the participants share a frustration that the global economic order is tilted in the west’s favour, and believe that now finally is the time to change it.

Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Barbados, spoke for many developing countries at a summit hosted by President Emmanuel Macron in June when she called for a transformation of the World Bank and IMF. “When these institutions were founded [in 1944] our countries did not exist,” she said.

Zoltan Pozsar, head of the macroeconomic advisory firm, Ex Uno Plures, believes that system is at a tipping point. “The global east and south are renegotiating the world order,” he says, highlighting the drive in the global south for de-dollarisation and a rethink of the IMF and World Bank.

The US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen has confidently pushed back against this, reflecting the view of many market participants that the ambition to dethrone the dollar as the global reserve currency is a very long-term bet. “There is a very good reason why the dollar is used widely in trade, and that’s because we have deep, liquid, open capital markets, rule of law and long and deep financial instruments,” she said at the Paris summit.

But politically at least the context is more propitious than ever to push for change. In the heyday of the cold war, the non-aligned movement had to rely on moral and emotional rather than economic or political clout. Now the Brics and aspirant members run an ever-larger share of the global economy and control many of the critical minerals the west so badly needs.

Moreover, some of the most influential “middle powers” who are wary of China share Beijing’s concerns over America’s weaponisation of financial sanctions. The signal moment for them in the past 18 months, argues the former Kofi Annan aide Mousavizadeh, was not Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 nor Nato’s rediscovery of its purpose, but the freezing of Russian central bank reserves, which dramatically underlined once again the power of the US dollar.

“Many thought we have to do whatever it takes to avoid being in the position of having reserves of this magnitude frozen in the future. That was Modi’s main response and many other middle power governments including in the Middle East were obsessed about this too.”

In Washington and west European capitals, officials are all focused on the rise of the middle powers and the need to reassess their world view. German officials even posit that Germany too can be seen as a middle power. “Our clear idea is that the world is not a G2 world,” said one. “It should be a multipolar world. The task of Germany could be more in the middle.”

At times the rhetoric emanating from Johannesburg will sound like a reheating of the old anti-imperialist language of Bandung. But western officials accept it would be wrong to dismiss it all out of hand as their 20th-century predecessors might have been tempted to do.

The age of the western set menu is over. And the new menu, while heavily influenced by two lead chefs, is still being written.

One interesting graph

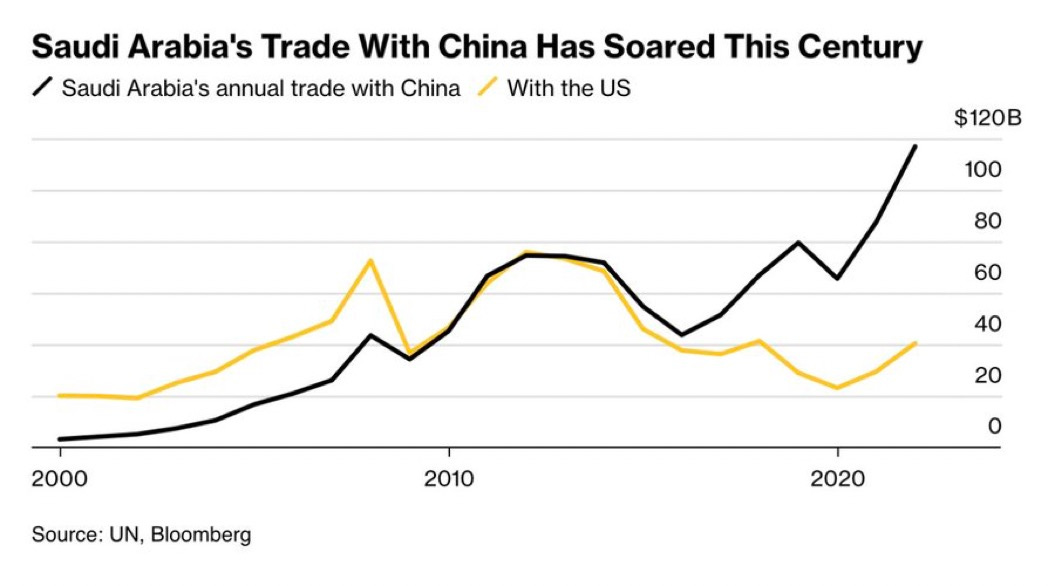

In keeping with today’s newsletter theme, new BRICS member and oil superpower Saudi Arabia’s trade with China has surged while trade with the US has lagged. This gives China more sway over the formerly staunch US ally.

Media recommendation

The latest health fad is dipping yourself in literal ice water and sitting in 175 F heat. Its surprisingly good for you, though doing so confirms you have too much time on your hands. In this week’s media recommendation, listen to why plus hear why Scandinavians store their babies in snowbanks.

There you have it, the seventh edition of Sunday Digest with the rise of a New World Order, growing Chinese influence in the Mideast, and Scandinavian ice babies. The portrait of a world spinning faster and faster. The good news is you have Netflix, Uber Eats, and running water. Until next time, be a good citizen, quit doomscrolling, and go outside.

Ad Astra Per Aspera!