Sunday Digest #8

Tribalism

Americans have gone through a Great Sorting over the past fifty years. We marry someone similarly educated, live among those of similar income, shop at the similar grocery stores, and our kids attend schools with similar kids. Algorithms amplify this trend and after a generation of dating app marriages, sorting is certain to be more extreme. The great political bands, the Democrats and Republicans, have followed MBA marketing 101 and targeted certain demographics, with great success.

Today, our warring political tribes are internally uniform. This has triggered human instincts deep in the reptile brain that fuel group behavior. If you ever look at US politics in 2023 and wonder how we got here, the reason is biology. The Wall Street Journal explores this in a recent article:

a potent driver of America’s partisan divide [is] group identity. Decades of social science research show that our need for collective belonging is forceful enough to reshape how we view facts and affect our voting decisions. When our group is threatened, we rise to its defense.

The split in the electorate has left many Americans fatigued and worried that partisanship is undermining the country’s ability to solve its problems. Calling themselves America’s “exhausted majority,” tens of thousands of people have joined civic groups, with names such as Braver Angels, Listen First and Unify America, and are holding cross-party conversations in search of ways to lower the temperature in political discourse.

Yet the research on the power of group identity suggests the push for a more respectful political culture faces a disquieting challenge. The human brain in many circumstances is more suited to tribalism and conflict than to civility and reasoned debate.

The differences between the parties are clearer than before. Demographic characteristics are now major indicators of party preference, with noncollege white and more religious Americans increasingly identifying as Republicans, while Democrats now win most nonwhite voters and a majority of white people with a college degree.

“Instead of going into the voting booth and asking, ‘What do I want my elected representatives to do for me,’ they’re thinking, ‘If my party loses, it’s not just that my policy preferences aren’t going to get done,” said Lilliana Mason, a Johns Hopkins University political scientist. “It’s who I think I am, my place in the world, my religion, my race, the many parts of my identity are all wrapped up in that one vote.”

More than 60% of Republicans and more than half of Democrats now view the other party “very unfavorably,” about three times the shares when Pew Research Center polled on it in the early 1990s. Several polls find that more than 70% within each party think the other party’s leaders are a danger to democracy or back an agenda that would destroy the country.

Party allegiance can affect our judgment and behavior, many experiments show. When Shanto Iyengar of Stanford University and Sean J. Westwood, then at Princeton University, asked a group of Democrats and Republicans to review the résumés of two fictitious high-school students in a 2015 study, their subjects proved more likely to award a scholarship to the student who matched their own party affiliation. People in the experiment gave political party more weight than the student’s race or even grade-point average.

In a landmark 2013 study, Dan Kahan, a Yale University law professor, and colleagues assessed the math skills of about 1,000 adults, a mix of self-described liberals, conservatives and moderates. Then, the researchers gave them a politically inflected math problem to solve, presenting data that pointed to whether cities that had banned concealed handguns experienced a decrease or increase in crime. In half the tests, solving the problem correctly showed that a concealed-carry ban reduced crime rates. In the other half, the correct solution would suggest that crime had risen.

The result was striking: The more adept the test-takers were at math, the more likely they were to get the correct answer—but only when the right answer matched their political outlook. When the right answer ran contrary to their political stance—that is, when liberals drew a version of the problem suggesting that gun control was ineffective—they tended to give the wrong answer. They were no more likely to solve the problem correctly than were people in the study who were less adept at math.

To explain why the animosity in American politics is greater today than in the past, some researchers have focused on the nation’s political “sorting”—the fact that Americans have shifted their allegiances so that the membership of each party is now far more uniform. In the past, each party had a mix of people who leaned conservative and liberal, rural residents and urbanites, the religiously devout and those less observant.

Data from the General Social Survey, a 50-year public opinion study run by NORC, a nonpartisan research group, shows that this is less the case today. Americans in the past were more likely to meet people different than themselves, which created opportunities for reducing group bias and creating conditions for compromise.

Today, our partisan identities have come into alignment with the other facets of our identity, which heightens our intolerance of each other even beyond our actual political disagreements, Mason said. Political party has become a “mega-identity,” she said, magnifying a voter’s political allegiances and amplifying the biases that innately come from belonging to a group.

“When you go to cast a ballot, whatever part of your identity is under the most threat is going to influence your choice the most,” Mason said.

One interesting graph

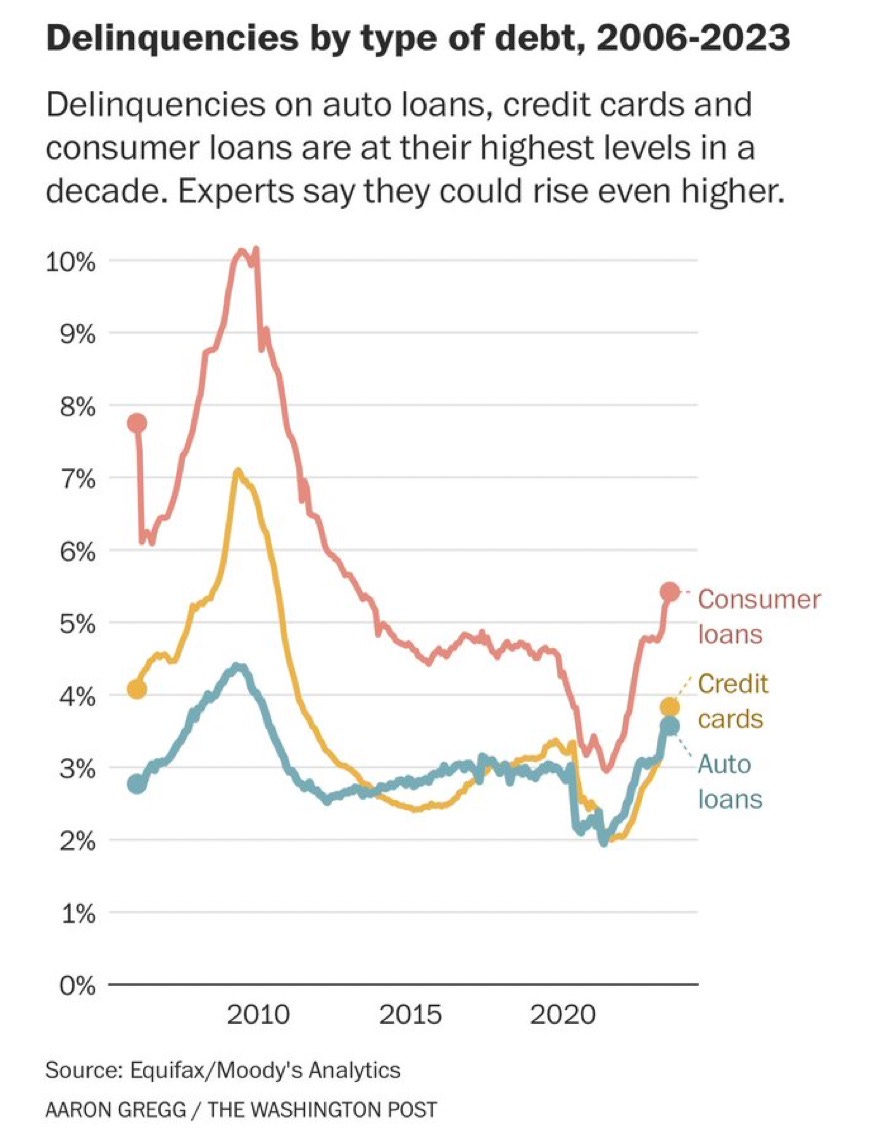

Americans got unprecedented transfer payments in the form of stimulus checks during the COVID-19 pandemic. This and a cessation of spending during the lockdowns led to a cushion of savings that has so far offset the corrosive impacts of inflation. But that may be starting to change as delinquencies on consumer credit card, auto, and other loans begin to spike, signaling possible consumer stress. Our economy runs on consumer demand so any pullback could trigger a recession.

Media recommendation

Netflix’s Quarterback follows Patrick Mahomes of the Chiefs, Kirk Cousins of the Vikings, and Marcus Mariota of the Falcons through the 2022 season, both on and off the field. The extreme access given to the Netflix cameras makes this required viewing even if you’re a casual NFL fan.

There you have it, the eighth edition of Sunday Digest featuring Americans in their primitive state, rising consumer loan delinquencies, and the lifestyles of NFL quarterbacks. The portrait of a world spinning faster and faster. The good news is you have Netflix, Uber Eats, and running water. Until next time, be a good citizen, quit doomscrolling, and go outside.

Ad Astra Per Aspera!