When it comes to the economy, size doesn’t always matter

Military strength isn’t always correlated with GDP

It’s a commonly held belief that military strength is directly correlated with economic size. If that’s the case, the USA ($23 trillion[i] GDP) is stronger than China ($18 trillion[ii] GDP) and far stronger than Russia ($2 trillion[iii]GDP). But is that true for an economy that’s 70%-80% services like the USA (hotels, restaurants, and iPhones made in China)? China is the world’s manufacturer and Russia outproducing the USA 3:1[iv] in artillery shells in Ukraine. The ammo shortage is so severe for the West that the USA is sending Ukraine cluster munitions, weapons banned by most allies and a move even newspapers friendly to the Biden Administration have criticized.

A recent article by Policy Tensor on Substack analyzes the relationship between GDP and military strength:

The idea that the economic size and industrial development of the powers was the decisive conditioner of war-making capabilities emerged from World War I. The dominance of firepower over mobility meant that wars would be wars of attrition fought along long, static fronts where prodigious quantities of munitions would be expended until one side capitulated. Unlike agrarian societies of similar demographic size, big industrial countries could field armies of several million men; armies that were voracious consumers of munitions, industrially manufactured war material, food and other supplies. Such massive armies could therefore be fielded for any appreciable length of time only by countries of great economic size and industrial strength.

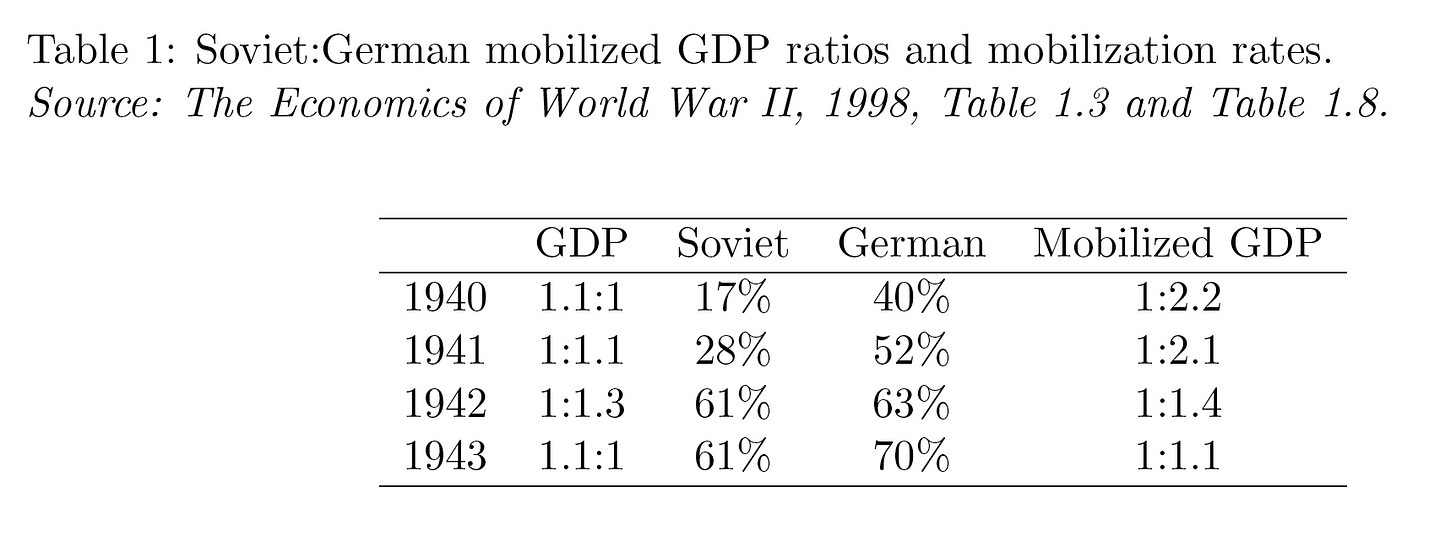

…on the Eastern Front the social scientific theory of war is unpersuasive, for the mobilized GDP ratios favored the Germans during the decisive phase of the Soviet-German war, 1941-1943. Harrison’s own data show that, as late as 1943, the ratio of Soviet to German mobilized GDP was 1.1, as was the ratio of raw GDP.

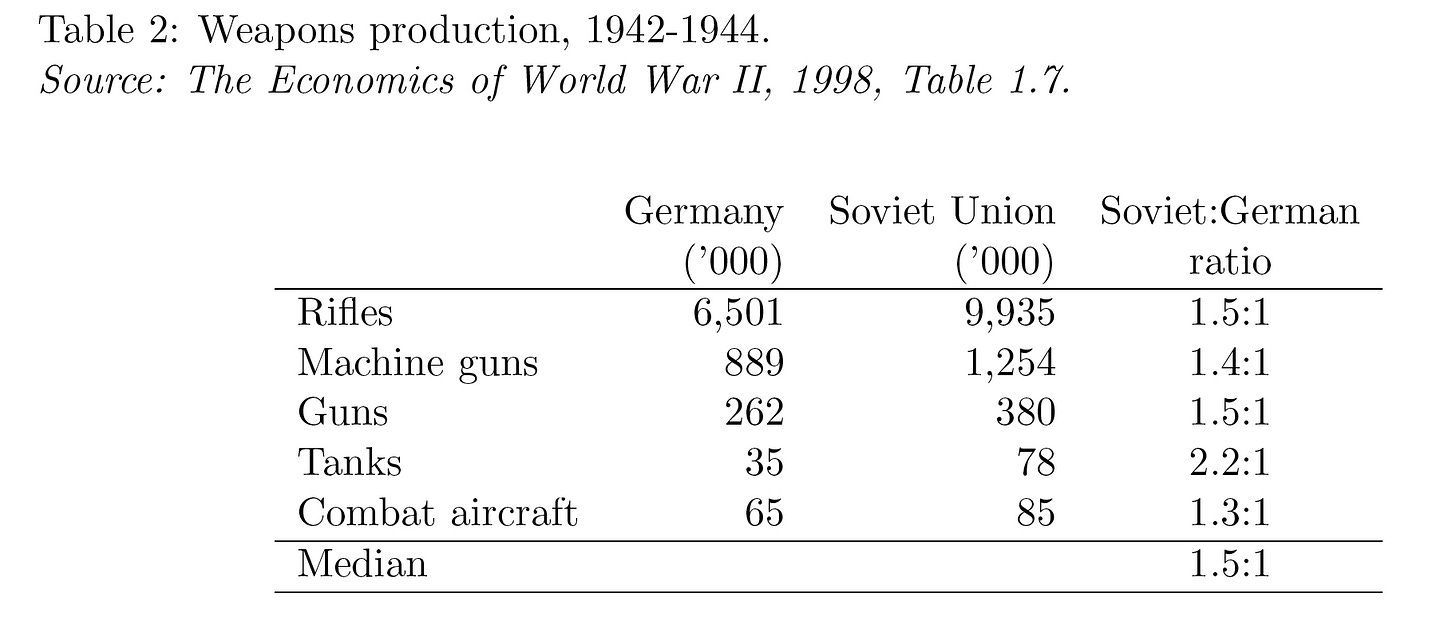

So, how did the Reds do it? Simple: the Soviets simply produced more weapons than the Germans. Even though the ratio of mobilized GDP was 1.1 in favor of the Germans, the ratio of weapons production was 1.5 in favor of the Soviets! (Both of these tables are from my “Western Perceptions of Soviet Strength in the Soviet-German War,” which was based on archival work in the O.S.S. archives under Adam Tooze’s supervision.)

The problem with the GDP fetish is that what really matters in protracted great power wars of attrition is not economic size per se, but defense-industrial production capacity. GDP serves as a good proxy only in as much as it captures variation in the latter. The position of your analyst is that, instead of using proxies like GDP, we need to directly interrogate the defense-industrial base. What does that say about the present balance of underlying war-making capabilities fielded for any appreciable length of time only by countries of great economic size and industrial strength.

Essentially, wars of attrition tested the capacity of the great powers to sustain the war effort for longer than their adversaries.

Electricity generation is a useful proxy of industrial scale. China surpassed the US around 2010. It now produces twice as much electricity as the United States.

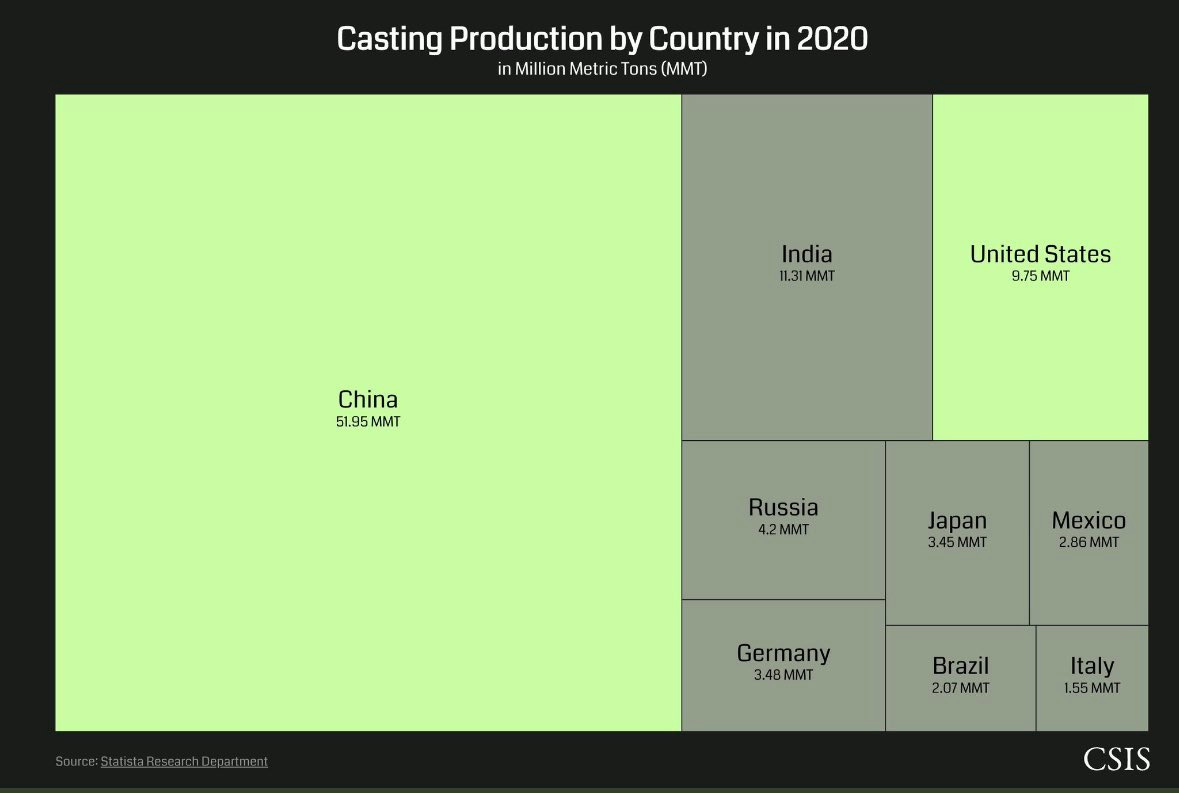

In Ukraine, we’ve seen how sustaining production of basic materials can be challenging. Specifically, there’s been a running crisis over the production of artillery shells. Even though every war since World War I has been, first and foremost, an artillery war, the tendency of Congress and the Services is to focus on sexy and expensive weapons systems to the neglect of basic capabilities. Now, the underlying capacity that is relevant to all such capabilities is the scale of casting production. China’s casting production in 2020 was five times as large as that of the United States’s. I’m greatly worried that the United States has let its defense-industrial base deteriorate while China’s has been growing in leaps and bounds.

The obvious solution to all this is to ramp up our defense-industrial base. But according to the AP, that will take 5 years and still be insufficient for Ukraine’s needs:

The Army is spending about $1.5 billion to ramp up production of 155 mm rounds from 14,000 a month before Russia invaded Ukraine to over 85,000 a month by 2028, U.S. Army Undersecretary Gabe Camarillo told a symposium last month. “Already, the U.S. military has given Ukraine more than 1.5 million rounds of 155 mm ammunition, according to Army figures. “But even with higher near-term production rates, the U.S. cannot replenish its stockpile or catch up to the usage pace in Ukraine, where officials estimate that the Ukrainian military is firing 6,000 to 8,000 shells per day. In other words, two days’ worth of shells fired by Ukraine equates to the United States’ monthly pre-war production figure.[v]

Assuming conservatively that Ukraine uses 6,000 shells per day, that’s 240,000 shells per month or about 3x what the US plans to produce in 2028. That is pathetic. WW2 lasted 4 years and the US mobilized to provide enough equipment to supply itself and its allies around the world. The Pentagon was built in 16 months. As previously mentioned on this Substack, it now takes longer on average to get an environmental permit (5 years) than the total time it took— from start to finish—to build the Hoover Dam. We must place a priority on rebuilding our defense industrial base.

I’ve said before that the USA has all the cards geopolitically and that our great power rivals China and Russia face headwinds. But a card player can misplay even a lucky hand.

[i] World Bank

[ii] World Bank

[iii] World Bank

https://twitter.com/davidsacks/status/1678463164864667658?s=42&t=nVb-5uC_WM3Cp0R0dGiqHQ

[v] AP