The dismal state of American healthcare has been a recurring topic on Ad Astra. Furthermore, the divide between rich and poor in health outcomes has been discussed but never in as much detail as in this week’s investigative report, conducted over a one year analysis of county-level data by the Washington Post. The study found that health, not wealth, is the best descriptor of inequality in modern America:

The United States is failing at a fundamental mission — keeping people alive.

After decades of progress, life expectancy — long regarded as a singular benchmark of a nation’s success — peaked in 2014 at 78.9 years, then drifted downward even before the coronavirus pandemic. Among wealthy nations, the United States in recent decades went from the middle of the pack to being an outlier. And it continues to fall further and further behind.

While opioids and gun violence have rightly seized the public’s attention, stealing hundreds of thousands of lives, chronic diseases are the greatest threat, killing far more people between 35 and 64 every year, The Post’s analysis of mortality data found.

Heart disease and cancer remained, even at the height of the pandemic, the leading causes of death for people 35 to 64. And many other conditions — private tragedies that unfold in tens of millions of U.S. households — have become more common, including diabetes and liver disease. These chronic ailments are the primary reason American life expectancy has been poor compared with other nations.

Sickness and death are scarring entire communities in much of the country. The geographical footprint of early death is vast: In a quarter of the nation’s counties, mostly in the South and Midwest, working-age people are dying at a higher rate than 40 years ago, The Post found. The trail of death is so prevalent that a person could go from Virginia to Louisiana, and then up to Kansas, by traveling entirely within counties where death rates are higher than they were when Jimmy Carter was president.

This phenomenon is exacerbated by the country’s economic, political and racial divides. America is increasingly a country of haves and have-nots, measured not just by bank accounts and property values but also by vital signs and grave markers. Dying prematurely, The Post found, has become the most telling measure of the nation’s growing inequality.

The mortality crisis did not flare overnight. It has developed over decades, with early deaths an extreme manifestation of an underlying deterioration of health and a failure of the health system to respond. Covid highlighted this for all the world to see: It killed far more people per capita in the United States than in any other wealthy nation.

Chronic conditions thrive in a sink-or-swim culture, with the U.S. government spending far less than peer countries on preventive medicine and social welfare generally. Breakthroughs in technology, medicine and nutrition that should be boosting average life spans have instead been overwhelmed by poverty, racism, distrust of the medical system, fracturing of social networks and unhealthy diets built around highly processed food, researchers told The Post.

The calamity of chronic disease is a “not-so-silent pandemic,” said Marcella Nunez-Smith, a professor of medicine, public health and management at Yale University. “That is fundamentally a threat to our society.” But chronic diseases, she said, don’t spark the sense of urgency among national leaders and the public that a novel virus did.

America’s medical system is unsurpassed when it comes to treating the most desperately sick people, said William Cooke, a doctor who tends to patients in the town of Austin, Ind. “But growing healthy people to begin with, we’re the worst in the world,” he said. “If we came in last in the next Olympics, imagine what we would do.”

The Post interviewed scores of clinicians, patients and researchers, and analyzed county-level death records from the past five decades. The data analysis concentrated on people 35 to 64 because these ages have the greatest number of excess deaths compared with peer nations.

What emerges is a dismaying picture of a complicated, often bewildering health system that is overmatched by the nation’s burden of disease:

· Chronic illnesses, which often sicken people in middle age after the protective vitality of youth has ebbed, erase more than twice as many years of life among people younger than 65 as all the overdoses, homicides, suicides and car accidents combined, The Post found.

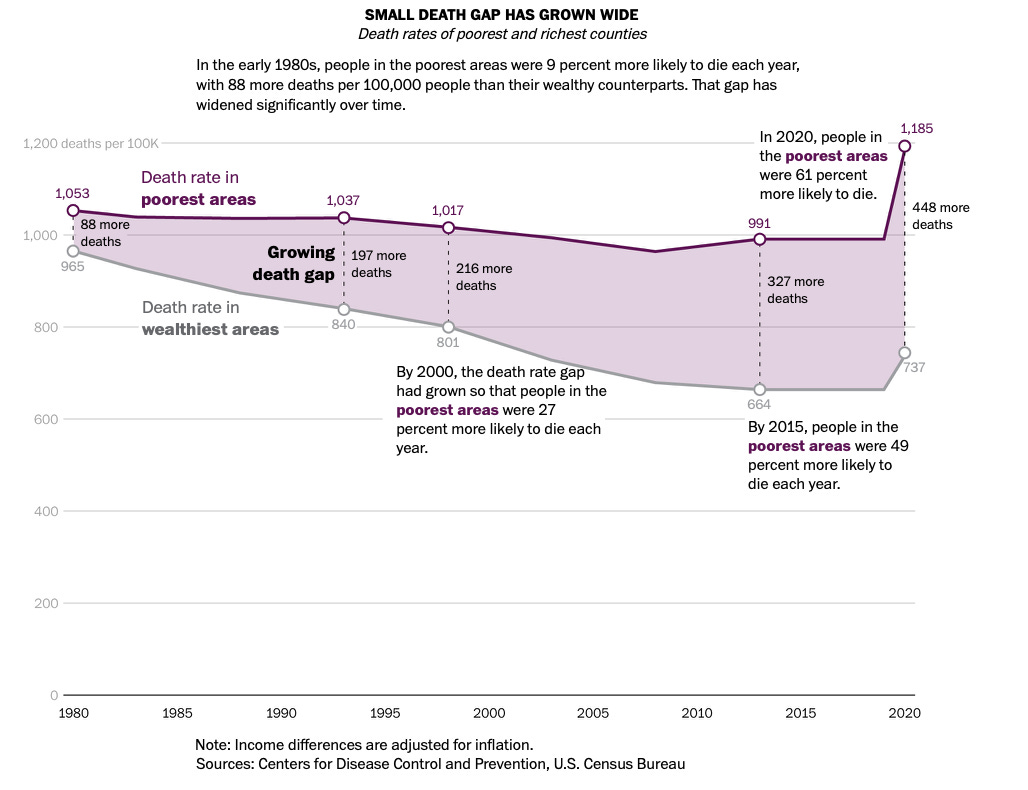

· The best barometer of rising inequality in America is no longer income. It is life itself. Wealth inequality in America is growing, but The Post found that the death gap — the difference in life expectancy between affluent and impoverished communities — has been widening many times faster. In the early 1980s, people in the poorest communities were 9 percent more likely to die each year, but the gap grew to 49 percent in the past decade and widened to 61 percent when covid struck.

· Life spans in the richest communities in America have kept inching upward, but lag far behind comparable areas in Canada, France and Japan, and the gap is widening. The same divergence is seen at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder: People living in the poorest areas of America have far lower life expectancy than people in the poorest areas of the countries reviewed.

· Forty years ago, small towns and rural regions were healthier for adults in the prime of life. The reverse is now true. Urban death rates have declined sharply, while rates outside the country’s largest metro areas flattened and then rose. Just before the pandemic, adults 35 to 64 in the most rural areas were 45 percent more likely to die each year than people in the largest urban centers.

In 1900, life expectancy at birth in the United States was 47 years. Infectious diseases routinely claimed babies in the cradle. Diseases were essentially incurable except through the wiles of the human immune system, of which doctors had minimal understanding.

Then came a century that saw life expectancy soar beyond the biblical standard of “threescore years and ten.” New tools against disease included antibiotics, insulin, vaccines and, eventually, CT scans and MRIs. Public health efforts improved sanitation and the water supply. Social Security and Medicare eased poverty and sickness in the elderly.

The rise of life expectancy became the ultimate proof of societal progress in 20th century America. Decade by decade, the number kept climbing, and by 2010, the country appeared to be marching inexorably toward the milestone of 80.

It never got there.

Partly, that is a reflection of how the United States approaches health. This is a country where “we think health and medicine are the same thing,” said Elena Marks, former health and environmental policy director for the city of Houston. The nation built a “health industrial complex,” she said, that costs trillions of dollars yet underachieves.

“We have undying faith in big new technology and a drug for everything, access to as many MRIs as our hearts desire,” said Marks, a senior health policy fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. “Eighty-plus percent of health outcomes are determined by nonmedical factors. And yet, we’re on this train, and we’re going to keep going.”

The opioid epidemic, a uniquely American catastrophe, is one factor in the widening gap between the United States and peer nations. Others include high rates of gun violence, suicides and car accidents.

But some chronic diseases — obesity, liver disease, hypertension, kidney disease and diabetes — were also on the rise among people 35 to 64, The Post found, and played an underappreciated role in the pre-pandemic erosion of life spans.

In 2021, according to the CDC, life expectancy cratered, reaching 76.4, the lowest since the mid-1990s.

The pandemic amplified a racial gap in life expectancy that had been narrowing in recent decades. In 2021, life expectancy for Native Americans was 65 years; for Black Americans, 71; for White Americans, 76; for Hispanic Americans, 78; and for Asian Americans 84.

Death rates decreased in 2022 because of the pandemic’s easing, and when life expectancy data for 2022 is finalized this fall, it is expected to show a partial rebound, according to the CDC. But the country is still trying to dig out of a huge mortality hole.

For more than a decade, academic researchers have disgorged stacks of reports on eroding life expectancy. A seminal 2013 report from the National Research Council, “Shorter Lives, Poorer Health,” lamented America’s decline among peer nations. “It’s that feeling of the bus heading for the cliff and nobody seems to care,” said Steven H. Woolf, a Virginia Commonwealth University professor and co-editor of the 2013 report.

In 2015, Princeton University economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton garnered national headlines with a study on rising death rates among White Americans in midlife, which they linked to the marginalization of people without a college degree and to “deaths of despair.”

Obesity:

In 1990, 11.6 percent of adults in America were obese. Now, that figure is 41.9, according to the CDC.

The rate of obesity deaths for adults 35 to 64 doubled from 1979 to 2000, then doubled again from 2000 to 2019. In 2005, a special report in the New England Journal of Medicine warned that the rise of obesity would eventually halt and reverse historical trends in life expectancy. That warning generated little reaction.

Obesity is one reason progress against heart disease, after accelerating between 1980 and 2000, has slowed, experts say. Obesity is poised to overtake tobacco as the No. 1 preventable cause of cancer, according to Otis Brawley, an oncologist and epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University.

Medical science could help turn things around. Diabetes patients are benefiting from new drugs, called GLP-1 agonists — sold under the brand names Ozempic and Wegovy — that provide improved blood-sugar control and can lead to a sharp reduction in weight. But insurance companies, slow to see obesity as a disease, often decline to pay for the drugs for people who do not have diabetes.

Why?

What happened to this country to enfeeble it so?

There is no singular explanation. It’s not just the stress that is such a constant feature of daily life, weathering bodies at a microscopic level. Or the abundance of high-fructose corn syrup in that 44-ounce cup of soda.

Instead, experts studying the mortality crisis say any plan to restore American vigor will have to look not merely at the specific things that kill people, but at the causes of the causes of illness and death, including social factors. Poor life expectancy, in this view, is the predictable result of the society we have created and tolerated: one riddled with lethal elements, such as inadequate insurance, minimal preventive care, bad diets and a weak economic safety net.

Public health experts point to major inflection points the past four decades — the 1990s welfare overhaul, the Great Recession, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, changes in the economy and family relationships — that have clouded people’s health.

Read much more at the Washington Post

Interesting chart

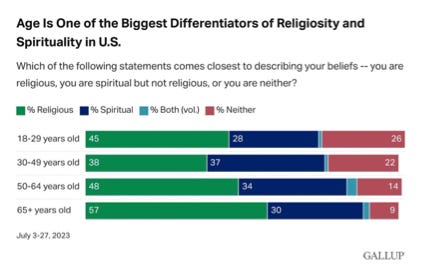

The decline of religiosity has been thought to be an inexorable, one-way downward trend in American life. But a new survey by Gallup shows that the percentage of people who consider themselves religious in the Gen Z cohort exceeds those in the Millennial cohort by 7%.

Media recommendation

This week, I recommend the Explorers Podcast, which provides very detailed accounts of explorers ranging from old world sailors, to mountaineers, to astronauts. The Explores Podcast reminds us of the innate human desire to seek out new frontiers through the ages.

#MotivationMonday 47: Zebulon Pike

There you have it, the thirteenth edition of Sunday Digest featuring an American healthcare calamity, religious Gen Zers, and humanity playing Marco Polo. The portrait of a world spinning faster and faster. The good news is you have Netflix, Uber Eats, and running water. Until next time, be a good citizen, quit doomscrolling, and go outside.

Ad Astra Per Aspera!