Welcome to the New Gilded Age

Part 4 of the American economy series focuses on how monopolies are rigging our industrial system, our markets and our democracy

Tl;dr

· Monopolies are omnipresent in our lives

· The last time monopiles were this prevalent in America was the Gilded Age (1865-1900)

· The current monopolization of our economy came from decades of deregulation and lax antitrust enforcement after the stagflation of the 1970s

· The consequences of this are firms that are Too Big To Fail, fragile supply chains and the corporate takeover of our lawmaking

· A handful of information monopolies – Big Tech – were allowed to form in the 1990s and 2000s

· Some think these information monopolies are a threat to our democracy

· There is a working, bipartisan coalition to take on monopolies in Congress

SUBSCRIBE HERE

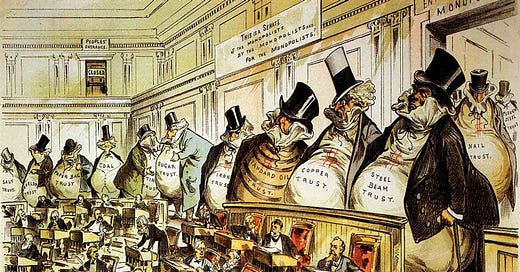

Figure 1: The Bosses of the Senate (1889)[i]

A Life Dominated by Monopolies

It’s Sunday morning and you roll over to check your phone ($AAPL). You scroll through Instagram to see what all of your friends did last night ($META). You see an ad that seems creepily personalized to you, but you quickly forget about it. You cut the cord, so you get your news from Google News and its algorithm ($GOOG). The news always seems to reinforce your existing views. You roll out of bed and realize your refrigerator is nearly empty. Time to place a grocery order with Amazon Fresh ($AMZN).

You have a flight to catch for work midday ($UAL). But before you grab a ride to the airport ($UBER), you have some time to kill and plop down on your couch for some TV ($NFLX). You scroll through the airline’s website to make sure you’re up to date with the current vaccine rules ($PFE). You’re good to go. You realize you haven’t paid your rent this month ($BX), so you log onto your apartment portal and pay with your credit card ($V).

This hypothetical morning is extreme, but is by no means hard to imagine. US history has been a running battle between monopoly power and the people for control of our republic since our founding. But during the height of corporate concentration in the Gilded Age, monopolies were nowhere near as ubiquitous in our daily lives as they are now. Standard Oil, the railroads, and other exploitive trusts were easy to classify as “bad monopolies”. In contrast, many of today’s monopolies make consumers lives easier and more efficient. That doesn’t make them any less dangerous.

The Gilded Age

The Gilded Age was a period of rapid economic growth after the end of the US Civil War (1865) until the turn of the twentieth century (1900). Railroads were the “tech disruptors” of the day and their westward push transformed the country. Like today, the political parties of the day were evenly matched and like today, they argued over cultural issues (prohibition), immigration, and economic issues (tariffs and the money supply). Inequality was extremely high and companies were highly concentrated into “trusts”.

The Industrial Revolution was in full swing and millions of factory jobs were created. Many of the new factory workers labored in dangerous conditions and were exploited by the trusts that employed them. A number of stories by journalists and books turned public opinion against the trusts, who dominated workers, the economy, and politics. Then in 1901, corporatist President William McKinley was assassinated and Theodore Roosevelt became President, leading one Senator to exclaim “that damned cowboy is President of the United States!”

Roosevelt took on the trusts, becoming known as the “trust-buster”. What came next became known as the Progressive Age and Theodore Roosevelt, and his successor William Taft, broke up many of the monopolies dominating the American economy. In all, Roosevelt brought 45 antitrust suits and Taft brought 75.[ii] Taft’s successor, Woodrow Wilson, created the Federal Trade Commission in 1914 to regulate antitrust in America.[iii]

Figure 2 : Net-zero factory during the Gilded Age

The Era of Globalization

In a way, the last 50 years mirror the Progressive Age, but in reverse. In a generation, we have unwound political economy reforms from the early twentieth century. It all started with an era of high gas prices, inflation, and slow economic growth (stagflation) in the 1970s. Jimmy Carter, who was a historically unpopular President, lost re-election to Ronald Reagan in 1980. Looking to jumpstart the economy, President Reagan deregulated large swaths of the economy and rolled back antitrust enforcement. It worked and the economy boomed in the 1980s. Deregulation continued apace on a bipartisan basis under Bill Clinton in the 1990s.

The successor to the Industrial Revolution, the Digital Revolution, enabled firms to communicate with factories anywhere in the world. This led to supply chains that wrapped around the globe, in a process known as globalization. It also led to the deindustrialization of America. In the absence of antitrust enforcement, firms gobbled one another up until cartels of three or four companies controlled entire industries. Profits boomed, especially in the 2010s after the Global Financial Crisis.

Figure 3: The CHASTINE MÆRSK entered the fleet in 1991

An Economy Dominated by Monopolies

Today we talk of Big Meat, Big Pharma, Big Media, Big Ag and others like they are natural features of our economy. Cable companies were allowed to consolidate into 3 firms, and cable bills rose at 8 times the rate of inflation to over $100 per month.[iv] Major pharmaceutical firms went from 60 to 10 between 2005 and 2017, and many of the acquisitions were justified economically by raising drug prices, sometimes as much as 6000%.[v] The most well-known case is Martin Shkreli the “Pharma Bro”, who raised prices per pill from $13.60 to $750[vi] (and seduced, then dumped the journalist who was covering him). Bayer bought Monsanto to consolidate global seed and pesticide manufacturers down to just 3, raising a bag of seed corn from $80 to $300.[vii] The global beer industry consolidated to a monopoly in 2016 when Anheuser-Busch InBev combined with SAB Miller.[viii] The group controls over 2000 beers, including Budweiser, Becks, Michelob, Corona and Stella Artois. In the US it controls over 70% of beer sales.

The labor movement of the 20th century was driven by poor working conditions and the exploitation of workers. Today, government regulations have addressed most of those issues. Today’s gig-workers are the exploited workers of yesterday. Gig-workers often lack benefits like healthcare or the wage to support a family.

Consequence 1: Too Big To Fail

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the bank bailouts, and the subsequent Fed action that destabilized our politics would not have happened if the banks weren’t allowed to consolidate until they were “Too Big To Fail”. Furthermore, the auto bailouts that left the US Federal Government nationalizing General Motors and Chrysler would not have been needed without excessive consolidation. The US taxpayer gave $50 billion to the airlines during the COVID-19 pandemic[ix]to prop them up, an amount made necessary because they were Too Big To Fail. Future crises are certain, and excessive consolidation makes industries weak and in need of taxpayer bailouts.

Consequence 2: Making Our Systems Fragile

In March 2021, the 20,000 TEU container ship the Ever Given got stuck in the Suez Canal for six days, blocking traffic in one of the most important arteries of the global economy. This incident exemplifies monopolization in the ocean shipping sector. To understand why it got stuck, you have to understand the economics of the shipping business.

Figure 4: The Ever Given blocking the Suez Canal[x]

Ever since the standard shipping container was invented in the 1960s, the goal has been achieving economies of scale. Ships have gotten bigger and bigger until the present. The Ever Given is the size of the Empire State Building - too big to sail. The ships have gotten so big that they are hard to steer and in this case, got stuck in a really inconvenient spot. As you can imagine, big ships are expensive and only very large firms can afford them. No problem, the shipping industry has consolidated. “There are eight dominant firms, all foreign-owned, and this year they are on pace to hit $100 billion in profit.”[xi] These big ships are difficult to maneuver, limiting the ports that can berth them to only the biggest, and cause operational problems when they offload due to the slug of containers they unleash. All of this together exacerbates the “supply chain delays” that have become a common part of our vernacular since COVID-19.

The nightmarish baby formula shortage in the spring of 2022 was also the result of excessive industry concentration:

A few months ago, a major producer of formula - Abbott Labs - shut down its main production facilities in Sturgis, Michigan, which had been contaminated with the bacteria Cronobacter sakazakii, killing two babies and injuring two others. Abbott provides 43% of the baby formula in the United States, under the brand names Similac, Alimentum and EleCare, so removing this amount of supply from the market is the short-term cause of the problem. (Abbott and Mead Johnson produce 80% of the formula in the U.S., and if you add in Nestle, that gets to 98% of the market.) The problem is not, however, that there isn’t enough formula, so much as the consolidated distribution system creates a lot of shortages in specific states.[xii]

Of course, you can’t have a supply chain crisis if your manufacturing hasn’t been offshored. It’s not small companies who have been shipping jobs overseas, it’s large multinationals. Large, global firms have been allowed to combine due to weak antitrust enforcement and have then relocated manufacturing to low-cost countries abroad. Monopolization has contributed to the deindustrialization of America.

Consequence 3: Corporate Capture of Our Lawmaking

A great example of the effect of the growth of corporate power over our lawmaking was discussed in Part 2 of this series, Legacy of the Great Recession. The responses to the parallel crises of the Great Depression and the Great Recession are revealing. In 1933, the Roosevelt Administration passed the 53-page Glass-Steagall Act, which outlawed many of the factors that led to the banking crisis. In the 2000s, banks had been allowed to consolidate into global behemoths and their lobbying infrastructure in Washington D.C. was immense. When the banks failed in 2008, the corrective action was the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, which was over 3,500 pages long and written by Wall Street lobbyists.

Figure 5: Schoolhouse Rock describes how corporate interests have co-opted our democracy

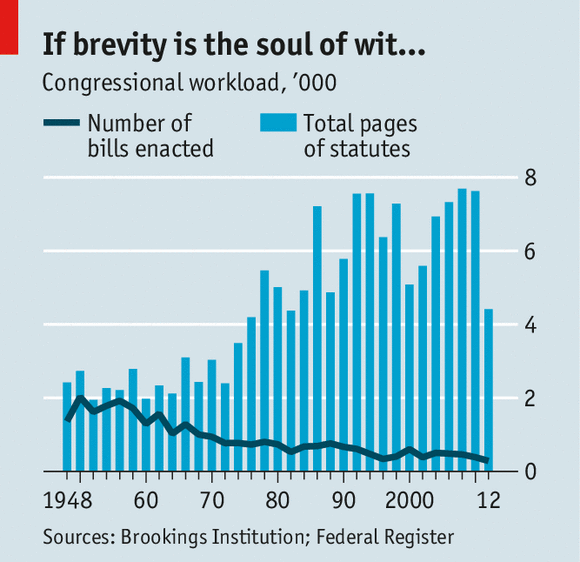

Some corporate lobbying is good, as the firms engaged in a given industry usually have subject-matter expertise. But if firms are allowed to a consolidate into powerful monopolies, their excessive influence can be in conflict with the public good. Spending on corporate lobbying has increased over the last century, to an all-time high of $3.7 billion in 2021.[xiii] As Figure 6 shows, the result has been more pages of legislation and fewer bills passed by Congress.

Figure 6: The inverse relationship between bill length and Congressional productivity[xiv]

Rise of Big Tech

The internet was brand new in the 1990s and the business models that supported internet companies were not well understood. Companies tended to start and fail quickly, with a 3-year-old firm considered mature in Silicon Valley. Companies like AOL, Netscape, and MySpace grew into household names and then failed quickly. The government didn’t know how to regulate these firms, so it didn’t.

Facebook was a social-networking firm founded in 2004. In the early 2010s an upstart called Instagram was founded that allowed users to easily share photos, a core feature of Facebook. The mobile UI was preferred by users to Facebook and the new platform was rapidly growing among Millennials, a huge demographic. Confronted by an existential threat to their business Facebook simply bought Instagram in 2012 for $1 billion. Facebook followed the same playbook in 2014 when they bought the messaging tool WhatsApp for $19 billion.

Figure 7: Facebook HQ

Facebook wasn’t the only internet company to use mergers to neutralize competitors. Google bought YouTube in 2006 for $2 billion. They then bought the rapidly growing Waze GPS navigation app for $1 billion in 2013 to integrate to their service Google Maps. All told, as of 2018 Facebook had acquired 67 competitors, Amazon 91, and Google 214. Today, these firms (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Google) form information trusts every bit as formidable as the goliaths from the Gilded Age.

Consequence 4: A Threat to Our Democracy

In its simplest form, a democracy is when voters ingest information and elect representatives to lead them based on how they interpret that information. Historically, independent journalists have fulfilled the role of interpreting the complex world and transmitting that information to voters. They funded their critical role by selling advertisements. But Big Tech’s ad-supported business is a far more efficient way to get ads to consumers, so journalism had to adapt their business model or die. The result has been a more sensationalist media, separate liberal and conservative media ecosystems, and the lack of a shared reality for liberals and conservatives in America.

Figure 8: Storms gather over the Capitol

If that wasn’t bad enough, Big Tech’s business model is essentially a market in human futures. What does that mean? Futures markets, like wheat futures, allow traders to bet on the future price of something. Human futures, allow companies to bet on the future behavior of humans. Big Tech has the ability to “nudge” people. If the algorithm thinks you are the type to like green juice, it will show you lots of ads for green juice. That’s valuable for companies selling green juice. Now suppose the tech platform can “nudge” just 1% of the 100 million users who might like green juice to buy some by showing them targeted ads after their phone GPS shows they visited the gym. That’s 1 million purchases of green juice and very valuable to sellers of green juice. Now imagine if those same techniques were applied to elections, which are often decided by a razor-thin margin.

This is not a hypothetical, we’re already there. Many Democrats were upset by the role that Twitter and Facebook played in the 2016 US Presidential election. Republicans were outraged by the censoring of a potentially election-changing story by Twitter and Facebook on the eve of the 2020 US Presidential election, which was determined by just 21,500 votes. Some liberals are upset over Elon Musk, who has expressed support for Republicans, and his plan to buy Twitter in 2022. This is not a Democratic or Republican issue, its an American issue. This country needs two well-informed parties to move forward, and Big Tech’s monopoly power over information is a threat to our democracy.

A Coalition to Take on Monopoly

These are big and daunting problems. Luckily, a bipartisan coalition exists in Congress to take on monopoly power. A bill to increase corporate merger filling fees – an administrative tweak – passed with both Democratic and Republican support 242-184 on September 29, 2022. Better yet, it could not have passed on party lines alone, it required both Democratic and Republican votes to pass. This means that a working coalition exists in Congress to take on monopoly power in future, more significant bills.

Figure 9: HR 3843 passes the House

Up Next

Thanks for reading how monopolies are rigging our system in this multipart series on the American economy. Up next is how rising higher education costs are creating an American Aristocracy.

If you want to learn more about monopolies, I recommend the Substack BIG by Matt Stoller.

[i] https://www.senate.gov/art-artifacts/historical-images/political-cartoons-caricatures/38_00392.htm

[ii] Wu, Tim. The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age. Columbia Global Reports, 2018.

[iii] https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/woodrow-wilson/

[iv] Wu, Tim. The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age. Columbia Global Reports, 2018.

[v] Ibid

[vi] Ibid

[vii] Ibid

[viii] Ibid

[ix] https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2021/12/14/airline-bailout-covid-flights/

[x] New York Times

[xiii] https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/03/12/lobbying-record-government-spending/

[xiv] The Economist