How To Fix Banks, Inflation, And The Economy Part 1: Banks

The current banking crisis has its roots in the 1980s, when Washington DC put the interests of Wall Street ahead of Main Street and can be brought to an end with Ad Astra’s plan

Tl;dr

· The current banking crisis has spread from America to the global financial system

· At its core, this crisis originates from Washington DC putting Wall Street ahead of Main Street since the 1980s

· Wall Street became a casino in the 1980s and the stock market boomed

· The stock market rally continued into the 1990s and early-2000s

· America has faced several so-called “black swans” in the last fifteen years

· Policymakers currently face a dilemma between further bank failures and resurgent inflation

· To save the banks, the economy needs structural reforms including reforming the Fed, breaking up Too Big To Fail banks, and restoring a vibrant small banking sector

Figure 1: Gordon Gekko of the 1987 film Wall Street

The banking system is in trouble again. The failure of SVB is the biggest bank failure since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008 and prompted the Fed to inject $300 billion into the financial system, more than double the emergency stimulus in 2020 at the onset of COVID-19[i]. Ad Astra’s overall diagnosis of this unfolding crisis is the implementation of neoliberal economic policies by both political parties since the 1980s that have put Wall Street ahead of Main Street. Said another way, we’ve become too focused on financial engineering, like the Fed’s monetary policy, and lost sight of the bricks and mortar economy. In this three-part series, we’ll explore ways we can address banks, inflation, and the underlying structure of the economy.

1. In Part 1: Banks, we’ll look at the recent history of finance and ways to strengthen banks

2. In Part 2: Inflation, we’ll examine how Great Depression levels of non-participation in the economy, including the people who never returned to the workforce after COVID-19, is fueling inflation

3. In Part 3: the Economy, we’ll conclude by exploring how banning stock buybacks would be one simple way to reverse the financialization of our economy

The unfolding crisis began with SVB in America, has spread to several other mid-sized US banks, and has gone global to Credit Suisse in Switzerland. So far, the crisis only exists in the financial markets (Wall Street), not in the real economy as exemplified by construction projects or barista jobs (Main Street). When in a healthy balance, Wall Street and Main Street work together to generate prosperity across the economy. But somewhere along the way Wall Street got too powerful to the detriment of Main Street. So how does a relatively small bank sneeze and the global financial system catch the flu? How did the economy get this fragile? That story begins in the 1980s with Gordon Gekko’s real-life counterparts.

Figure 2: Compared to other crisis over the last 40+ years, this is a major banking crisis[ii]

1980s: The Origins Of Neoliberalism

Coming out of the 1970s, a decade of major economic trouble, the public demanded reforms. Neoliberalism was the result. Neoliberalism rests on 3 pillars: privatization, deregulation, and financialization. Some examples of privatization include the air traffic control system, prisons, electric utilities, and toll roads, which were all transferred from the government to private operators. Examples of deregulation included the airlines, railroads, trucking, and banking. Examples of financialization include “financial innovations” such as derivatives and stock buybacks. As a rule, “financial innovations” are always bad and cause calamity at some point in the future. In the meantime, the stock market boomed.

Figure 3: Stock market liftoff in the 1980s

One “financial innovation” was the development of bond trading. What was once a sleepy market where investors bought and held company debt to maturity for several years became a high stakes casino game. Traders like convicted felon Michael Milken and international fugitive Marc Rich became celebrities. The widespread availability of cheap debt spawned corporate raiding, now euphemistically called private equity (PE). Since interest rate changes greatly affect the value of bonds, people began to care more about the Fed’s monetary policy than the real economy. The Wall Street bonanza influenced the culture and the movies Wall Street, American Psycho, and Wolf of Wall Street are all set in the period. The classic 1987 book Bonfire of the Vanities by Tom Wolfe is about a bond trader during the period.

Figure 4: (clockwise from top) Patrick Bateman in “American Psycho”, Jordan Belfort in “Wolf of Wall Street”, and Gordon Gekko in “Wall Street”

To The Moon!

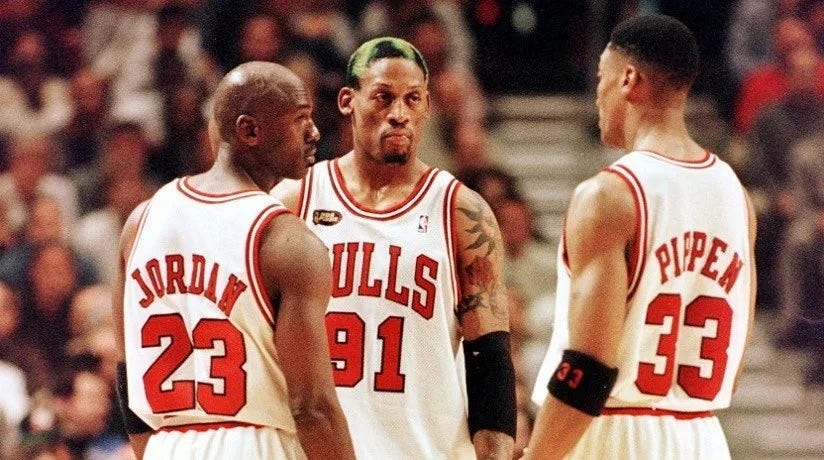

The early 1990s were a heady time in America: the Soviets were beaten, the Chicago Bulls were ascendant, and a young governor from Arkansas had won the presidency.

Figure 5: 1990s Chicago Bulls

Alan Greenspan was the Fed Chairman and so Wall Street friendly that he was nicknamed “The Man Who Knew” in reference to his ability to increase markets. Wall Street chummy policy emanated from the Fed and elected leaders of both parties. The stock market continued its exponential increase.

Figure 6: Stock market performance through 2000

Meanwhile on Main Street, the repercussions of several events were not fully considered. The USA joined NAFTA and China joined the WTO, which would combine to tear the industrial heart out of America by the 2010s. Easy money policy by the Fed inflated a massive housing bubble that nearly brought down the global financial system in 2008.

Crises

A “black swan” is an event so exceedingly rare that it only happens once-a-century but has consequences that are severe. Since we’ve had three “black swans” in the last fifteen years, we either mischaracterized these events or are really unlucky.

Figure 7: The "black swan"[iii]

The first so-called “black swan” was the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. As Ad Astra has already detailed, our response was to drop interest rates to zero and print money. There were no structural changes; all Wall Street and no Main Street. Instead of breaking up the Too Big To Fail banks that caused the catastrophe, we passed the toothless Dodd-Frank bill, which compares poorly to FDRs actions during the Great Depression:

FDR closed the banks, passed a banking reform bill called the Glass-Steagall Act that was 53 pages long, and indicted several Wall Street executives for fraud in public hearings.

In contrast, the Obama Administration bailed out the Too Big To Fail banks, indicted zero Wall Street executives for fraud, and passed a 3,500+ page Dodd-Frank banking reform act written by Wall Street lobbyists.[iv]

The next “back swan” was the COVID-19 pandemic. Again, we resorted to printing money, a tactic Wall Street loves.

In fact, the Fed printed more money in a month than in two centuries of American history.[v]

Figure 8: US money supply after COVID-19

The latest “black swan” is the failure of SVB.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell issued a joint statement Sunday evening stating that depositors in SVB would be kept whole and that the Fed would essentially backstop all uninsured deposits in regional banks across the US.[vi]

The Fed’s “backstop” so far is worth $300 billion of you guessed it, printed money. The immediate concern is that without reform, deposits in regional and community banks will be withdrawn and put into Too Big To Fail banks on Wall Street.

The Current Pickle

Today, we find ourselves in quite a predicament. The Fed can either raise interest rates further to tame inflation but blow up the banks. Or the Fed can lower interest rates to save the banks but stoke inflation. In either scenario a recession is likely as credit conditions tighten.

Figure 9: The Fed's impending doom

The Way Out

The good news is there is a fix but the bad news is that it isn’t hitting the easy button and printing more money. It will take time.

Figure 10: The easy button

To save the banking sector we need structural reforms that balance the interests of Main Street and Wall Street. Specifically:

1. Reform the Fed

2. Break up the Too Big To Fail banks

3a. Congress should pass new rules that support a vibrant small banking sector and allow banks to fail without jeopardizing the entire system

3b. Temporarily guarantee all deposits until 3a is complete

Over the past fifteen years, the Fed has proven its incompetence regardless of Chairperson. The Fed currently has responsibility for bank supervision, which clearly failed in the case of SVB. Responsibility for supervising banks should be given to the Federal Deposits Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which already is on the hook for insuring deposits (aligning incentives).

If 2008 didn’t convince you, in the 1930s the cooperation of large, centralized banks enabled the fascist regimes of Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany to tightly control their populations[vii]. Too Big To Fail banks are bad. They make the financial system fragile, foster crony capitalism, and will necessitate future bailouts. We should break up the largest banks so that none are Too Big To Fail.

To protect against the so-called “black swans” that we know will come, we need a resilient banking sector that won’t be threatened by one-off bank failure. In 1971, there were 13,612 banks in the country. Fifty years later, in 2021, there were only 4,237 banks.[viii] America needs thousands of small banks where you can discuss the community with your banker and where your money won’t be bet in the Wall Street casino. Congress should pass new rules that support a vibrant small banking sector, increase FDIC limits commiserate with inflation, and allow banks to fail without jeopardizing the entire system.

To stem the near-term flow of deposits from small banks to the Too Big To Fail Wall Street monopolies, the federal government should TEMPORARILY guarantee all deposits system-wide. It should be made clear up front that this measure is temporary and will be lifted as soon as reforms from Congress are passed.

All of this falls under 1. Level the playing field in Ad Astra’s 5-point plan to restore the American Dream.

Up next

This series will continue in Part 2: Inflation, where we’ll examine how Great Depression levels of non-participation in the economy, people who have stopped looking for work, is fueling inflation.

[ii] https://on.ft.com/3n6rlEW

[iii] https://theoryofinterest.blogspot.com/2017/01/the-outside-context-problem.html

[viii] https://www.lynalden.com/march-2023-newsletter/