How To Fix Banks, Inflation, And The Economy Part 2: Inflation

The economy needs structural reform of the workforce, not more financial engineering, to reduce inflation

Tl;dr:

· There is currently a labor shortage in America, which is driving inflation

· The Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR) measures the total number of people in the workforce, including those who stopped looking for work

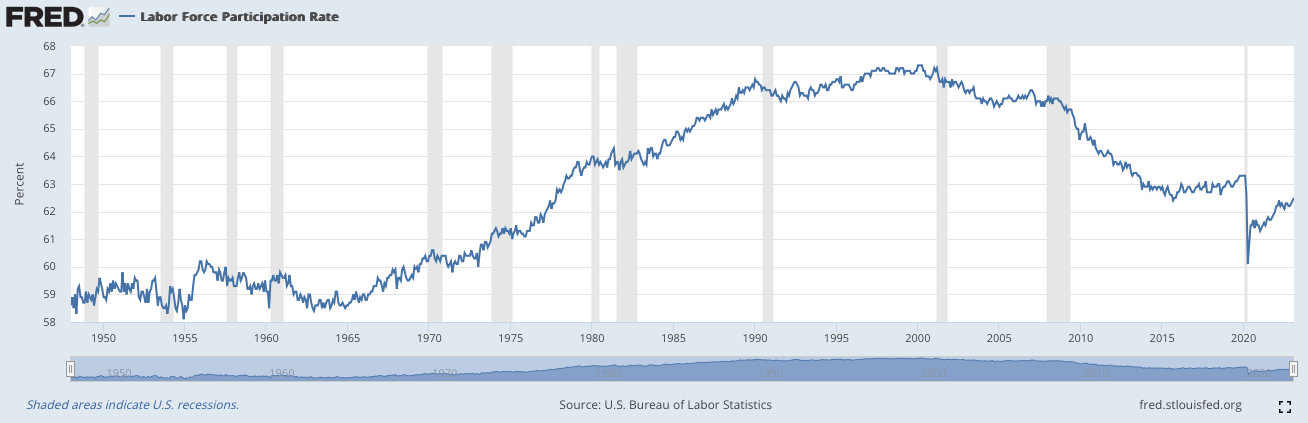

· The US LFPR peaked in the late 1990s, before declining in the early 21st century and plummeting after the COVID-19 pandemic

· The male-only LFPR has been declining since the 1960s and is currently at Great Depression lows due to overly generous welfare policies and over-incarceration

· To increase the available workforce and reduce inflation we should 1) reform welfare (using the upcoming debt ceiling negotiations to make a deal), 2) reform the criminal justice system, and 3) deploy AI to boost labor productivity

· We should also reform the higher education system and make older workers productive longer

Rosie the Riveter has become an avatar for the domestic US WW2 industrial mobilization and for the feminist movement more broadly. She symbolized the millions of women who entered the workforce to fill vacant and new jobs supporting the men fighting the war overseas. After the atom bomb was dropped on Nagasaki in August 1945, the war ended but these women did not all leave the workforce. The 1960-1970s brought much social change, with the women’s liberation movement supercharging female entry into the workforce. Their entry continued before peaking in the 1990s. The percentage of women in the workforce has largely remained stable in the 2000-2010s. Then COVID-19 struck and millions of women, and men, left the workforce.

In this three-part series, we are exploring ways to address banks, inflation, and the underlying problems in the structure of the economy.

1. In Part 1: Banks, we looked at the recent history of finance and ways to strengthen banks

2. In Part 2: Inflation, this post, we’ll examine how Great Depression levels of non-participation in the economy, including the people who never returned to the workforce after COVID-19, is fueling inflation

3. In Part 3: the Economy, we’ll conclude by exploring how banning stock buybacks would be one simple way to reverse the financialization of our economy

Inflation in America, rising prices for all goods and services, hit a forty-year high in 2022 and is still elevated. A large component of the prices you pay are labor costs. Of the $5 latte you buy from Starbucks, the paper cup and coffee is pennies compared to the $15 hourly wage of the barista who prepared it. America is currently experiencing a labor shortage, meaning businesses cannot find the help they need. This dynamic puts upward pressure on wages, as firms must pay more to hire workers. Higher wages pass through to the consumer and drive inflation in a vicious cycle. The large chunk of workers who left the workforce during COVID-19 and the largely unreported millions of able-bodied, working age men who left the workforce in the decades prior are fueling inflation and will be the topic of this post.

Figure 1: The number of job openings nearly doubles the available workers[i]

What is the LFPR?

The media and politicians highlight the monthly unemployment rate to assess economic performance, but this is the wrong metric. The proper metric (or at least a necessary companion to the unemployment rate) is the Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR). The unemployment rate only measures those who are actively looking for work while the LFPR measures all working-age people, even those who have stopped looking for work.

Here is a video explaining the difference between the unemployment rate and the LFPR.

US LFPR

The US LFPR climbed from WWII due to millions of women entering the workforce as described at the beginning of this post. However, after peaking in the late 1990s at nearly 68%, it has fallen to less than 63% today (a drop of tens of millions of workers).

Figure 3: US LFPR from 1950-present[ii]

The US LFPR took a massive hit in 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ad Astra previously discussed this drop:

due to COVID-19, which caused more than 3 million between the ages of 55 and 65 (Baby Boomers) to retire early and leave the workforce as part of the Great Resignation. They had many reasons for retiring early, but in general the combination of COVID hassles and sufficient retirement savings made them decide to retire…And it negatively impacted the labor supply so even a business that wanted to generate economic activity by hiring someone couldn’t find workers. Perhaps you’ve noticed shops or restaurants randomly closed recently.[iii]

As of the beginning of 2023, it is estimated that there would be 2.8 million more workers in the labor force had COVID-19 never occurred.

Figure 4: 2.8 million worker hole in the labor force[iv]

Men Without Work

But COVID-19 is not solely to blame for the labor shortage and inflation. The male-only LFPR has been declining from the 1960s to today, from over 85% to under 70%.

Figure 5: Male-only LFPR[v]

This downward trend has been masked by the positive effect of women entering the workforce (Rosie the Riveter), and has gone largely unnoticed. Today, the male LFPR is at Great Depression lows.

Causes

Some attribute this decline to young men getting high and playing Call of Duty. That may contribute to some decline in the LFPR but that’s not the full story. Furthermore, the overall wealth accumulated by some families in America enables some men not to work. But that too is incomplete. Data are not comprehensive but there are two addressable factors causing the decline in male LFPR: 1) overly generous welfare and disability safety net policies and 2) excessive felony conviction and incarceration.

Ad Astra discussed the bloating of the disability rolls in The Sickening of America:

There are many reasons why the LFPR is lower today than in 2000 but one reason is the increased number of people who aren’t working due to chronic illness or a disability. Since work and the world are no more dangerous than in the past (in fact, the opposite is true) the rate of disability should not be up. But it is. Our failing system has left people sick, disabled, and unable to work. There are about 6 million more people with a disability in 2023 than in 2008, the first year the government tracked this statistic.[vi]

While America accounts for 4.25% of the world’s population, it makes up 22% of the global prison population.[vii] There are not reliable figures on the ex-felon population in the US, but it is thought that 1 in 3 Americans have a criminal record with at least some portion of this subset being ex-felons.[viii] These people have trouble getting hired, and many stop looking for work.

Recommended Actions

1. Reform the welfare and disability safety net to eliminate perverse incentives

2. Reform the criminal justice system and pass laws to re-integrate ex-felons into society

3. Increase labor productivity with Artificial Intelligence (AI)

First, Congress must investigate welfare and disability programs to understand why they have driven people out of the workforce. They should then pass laws to reform these programs and eliminate perverse incentives not to work. The upcoming debt ceiling negotiations would be an excellent opportunity to do this.

Second, society must take steps to reduce felony conviction rates without compromising public safety. Furthermore, we must take steps to re-integrate ex-felons into the workforce. An example might be giving tax credits to businesses that hire non-violent ex-felons.

Third, there is understandable anxiety about AI taking all our jobs but in all of human history, new technologies have never reduced employment. The invention of the car rendered buggy drivers obsolete, but the new jobs making tires, gasoline, and other automobile parts more the compensated. AI will make existing workers more productive, easing the labor shortage and inflation.

We also made two recommendations on how to increase the workforce in a previous post:

1. Reform the higher education system

2. Make older workers productive longer

One of the key problems of the current American labor shortage is the job openings gap: there are more job openings than people who are unemployed and seeking work. This implies that the current unemployed don’t have the right skills to fill the open jobs. Additionally, currently employed persons aren’t as prepared for their jobs as they could be. In economic theory, increasing the education of the labor supply increases labor productivity. A more productive workforce is a key component of making a healthy economy. This doesn’t even consider the exorbitant (and increasing) cost of higher education in America. Higher education is broken in the US, that is a drag on the economy, and will be a future topic on this Substack.

In order to make do with the workforce we have, we need to keep older workers productive longer. For example, my mom is 64 and still teaches fitness classes at the YMCA. I don’t expect her to retire at 65*. For some like her, this is a choice. Others may need to be incentivized to stay in the workforce with flexible work arrangements, increased benefits or other perks. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) already assumes this will happen in their workforce forecasts. The number of people 65-69 participating in the workforce in 2000 was 24.5%. By 2030, that figure is expected to reach 39.6%[ix].[x]

Taken together, these steps along with drastically increasing American energy production will reduce inflation.

These steps fall under 2. Make the US worker competitive in Ad Astra’s 5-point plan to reignite the American Dream.

Up Next

In Part 3: the Economy, we’ll conclude by exploring how banning stock buybacks would be one simple way to reverse the financialization of our economy.

*Update: my mom turned 65 last Friday and didn’t retire from the YMCA

[i] https://www.uschamber.com/workforce/understanding-americas-labor-shortage

[ii] St. Louis Fed

[iv] https://www.uschamber.com/workforce/understanding-americas-labor-shortage

[v] St. Louis Fed

[vii] ChatGPT

[viii] ChatGPT

[ix] BLS